Discourses of Muslim Scholars in Colonial Ghana

by John Hanson and Muhammad al-Munir Gibrill

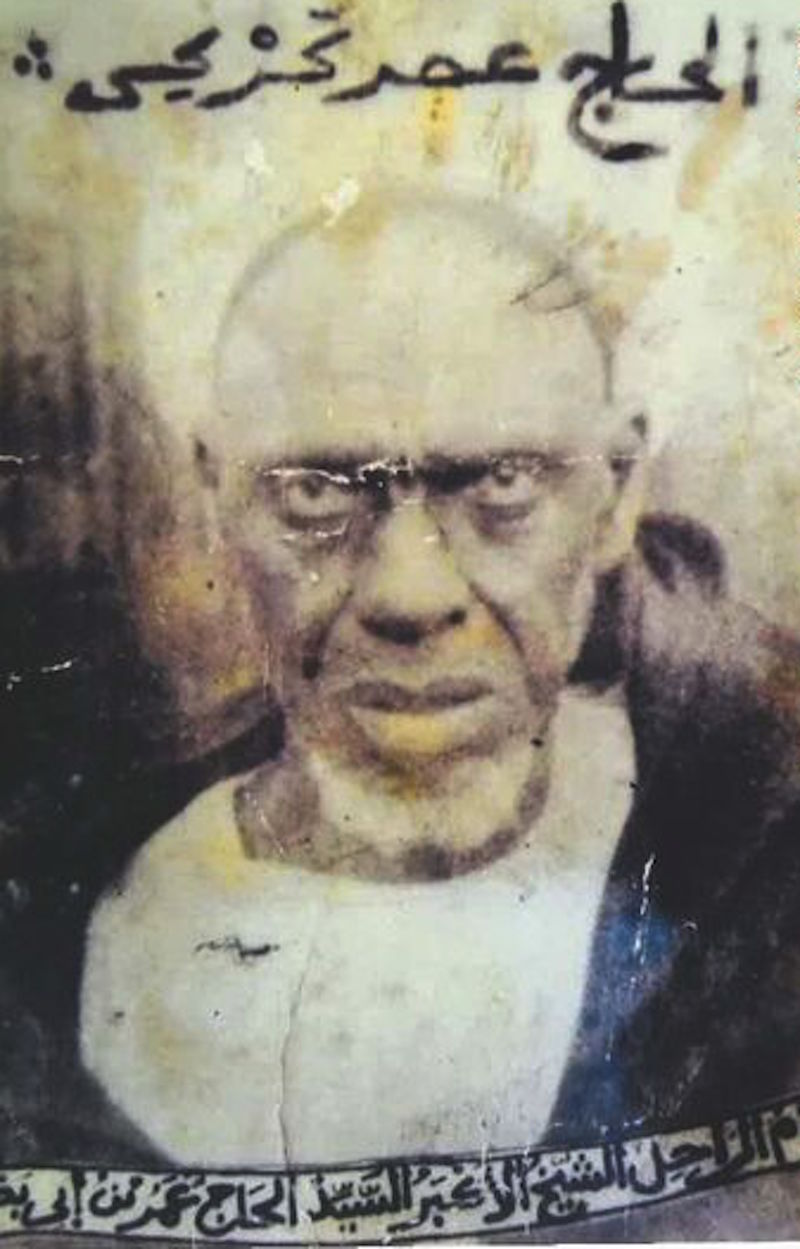

Biography of Al-hajj 'Umar

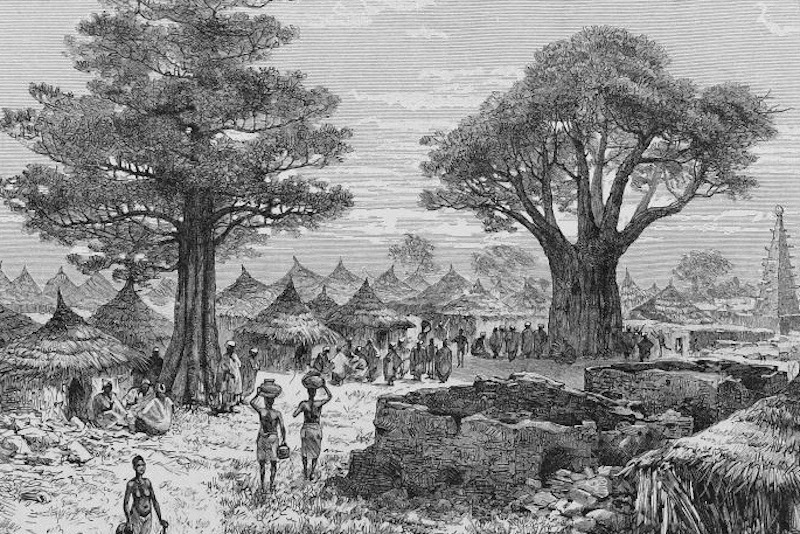

Al-ḥājj 'Umar ibn Abī Bakri was born in the mid-nineteenth century at Kano, the largest town in the Sokoto Caliphate. His father, Abī Bakri, was from Kebbi and his mother, Maimunatu, was from Kano. Al-ḥājj 'Umar's father was a kola merchant with operations in Kano and Salaga, a commercial town in the Gonja state in the upper Volta basin. While al-ḥājj 'Umar studied with eminent Muslim scholars and became quite learned, he also remained involved in his family’s commercial enterprise, especially when his father died in the early 1880s. Al-ḥājj 'Umar moved to Salaga, where two brothers already resided, to manage the business. Shortly after his move to Salaga, a civil war broke out. Al-ḥājj 'Umar fled Salaga and, after a brief period of itinerancy, settled in 1896 at Kete-Krachi, a town located a hundred miles southeast of Salaga. Kete-Krachi was two distinct settlements: Krachi was the residence of the political elite and other indigenous inhabitants of the region, and Kete was a suburb where Hausa and other Muslim migrants resided.

Kete-Krachi was in the German colonial sphere in the late nineteenth-century. Shortly after al-ḥājj 'Umar settled in Kete, German colonial officials realized that al-ḥājj 'Umar was a more qualified Muslim scholar than the local imam of town: they eventually appointed al-ḥājj 'Umar in this role. Al-ḥājj 'Umar was a cultural intermediary: he developed a working relationship with the German official Adam Mischilch, who studied under al-ḥājj 'Umar to learn Hausa and the history of West African Muslims. Al-ḥājj 'Umar wrote numerous works for Mischilch, who returned to Germany to compose several books and articles from what he learned. German officials appointed one of al-ḥājj 'Umar's students to serve as the head of Kete. With this turn of events, al-ḥājj 'Umar was a person of influence and remained at Kete-Krachi for the rest of his life.

Al-ḥājj 'Umar was one of the preeminent Muslim scholars of his era. At Kete-Krachi he organized a Muslim school and attracted numerous students to study with him. He also went on the pilgrimage to Mecca, gaining the honorific title of al-ḥājj, in travels to Arabia between 1913 and 1918. The pilgrimage to Mecca in the 1910s led to al-ḥājj 'Umar become a leader in the Tijāniyya Sufi order. In Mecca al-ḥājj 'Umar met the West African scholar Alfa Hashīm, a nephew of al-ḥājj 'Umar Taal of Futa Toro, who propagated this branch of Sufism in West Africa. Alfa Hashīm was a muqaddam, a title for a Sufi Muslim with the ability to initiate others into the order, and Alfa Hashīm bestowed this status upon al-ḥājj 'Umar of Kete-Krachi, and he emerged as a major Sufi master in West Africa upon his return. Al-ḥājj 'Umar taught his disciples special prayers that heightened their spiritual consciousness and stressed living a pious life. He also wrote poetry that expressed Sufi themes of encountering previous Sufi saints and even the Prophet Muḥammad in mystical encounters.

Kete-Krachi entered a new era at the end of the First World War. Britain and France took control of German colonial territories in Africa after the war, with Kete-Krachi falling into British hands. Al-ḥājj 'Umar developed relations with British colonial officials, especially with the British official A.C. Duncan-Johnstone, who held various positions in the 1920s and early 1930s. Duncan-Johnstone appointed one of al-ḥājj 'Umar's students, Malam Salaw, to be the head of the Muslim community in Kumase in the 1920s. Al-ḥājj 'Umar's influence thus continued in the British colonial era until his death in 1934.

These experiences provided al-ḥājj 'Umar with insights into the European colonial era. Initially shaken by events, he came to understand various aspects of the colonial consolidation under the Germans and then the British. He viewed these developments through the prism of a Muslim scholar steeped in the knowledge and attitudes of West African Muslims with connections to other parts of the Muslim world. His writings reflect his sense of loss as well as his desire to make the most of new circumstances under colonial rule.

Kete-Krachi was in the German colonial sphere in the late nineteenth-century. Shortly after al-ḥājj 'Umar settled in Kete, German colonial officials realized that al-ḥājj 'Umar was a more qualified Muslim scholar than the local imam of town: they eventually appointed al-ḥājj 'Umar in this role. Al-ḥājj 'Umar was a cultural intermediary: he developed a working relationship with the German official Adam Mischilch, who studied under al-ḥājj 'Umar to learn Hausa and the history of West African Muslims. Al-ḥājj 'Umar wrote numerous works for Mischilch, who returned to Germany to compose several books and articles from what he learned. German officials appointed one of al-ḥājj 'Umar's students to serve as the head of Kete. With this turn of events, al-ḥājj 'Umar was a person of influence and remained at Kete-Krachi for the rest of his life.

Al-ḥājj 'Umar was one of the preeminent Muslim scholars of his era. At Kete-Krachi he organized a Muslim school and attracted numerous students to study with him. He also went on the pilgrimage to Mecca, gaining the honorific title of al-ḥājj, in travels to Arabia between 1913 and 1918. The pilgrimage to Mecca in the 1910s led to al-ḥājj 'Umar become a leader in the Tijāniyya Sufi order. In Mecca al-ḥājj 'Umar met the West African scholar Alfa Hashīm, a nephew of al-ḥājj 'Umar Taal of Futa Toro, who propagated this branch of Sufism in West Africa. Alfa Hashīm was a muqaddam, a title for a Sufi Muslim with the ability to initiate others into the order, and Alfa Hashīm bestowed this status upon al-ḥājj 'Umar of Kete-Krachi, and he emerged as a major Sufi master in West Africa upon his return. Al-ḥājj 'Umar taught his disciples special prayers that heightened their spiritual consciousness and stressed living a pious life. He also wrote poetry that expressed Sufi themes of encountering previous Sufi saints and even the Prophet Muḥammad in mystical encounters.

Kete-Krachi entered a new era at the end of the First World War. Britain and France took control of German colonial territories in Africa after the war, with Kete-Krachi falling into British hands. Al-ḥājj 'Umar developed relations with British colonial officials, especially with the British official A.C. Duncan-Johnstone, who held various positions in the 1920s and early 1930s. Duncan-Johnstone appointed one of al-ḥājj 'Umar's students, Malam Salaw, to be the head of the Muslim community in Kumase in the 1920s. Al-ḥājj 'Umar's influence thus continued in the British colonial era until his death in 1934.

These experiences provided al-ḥājj 'Umar with insights into the European colonial era. Initially shaken by events, he came to understand various aspects of the colonial consolidation under the Germans and then the British. He viewed these developments through the prism of a Muslim scholar steeped in the knowledge and attitudes of West African Muslims with connections to other parts of the Muslim world. His writings reflect his sense of loss as well as his desire to make the most of new circumstances under colonial rule.

Images

Images