Failed Islamic States in Senegambia

David Robinson

Umar Tal or al-hajj Umar

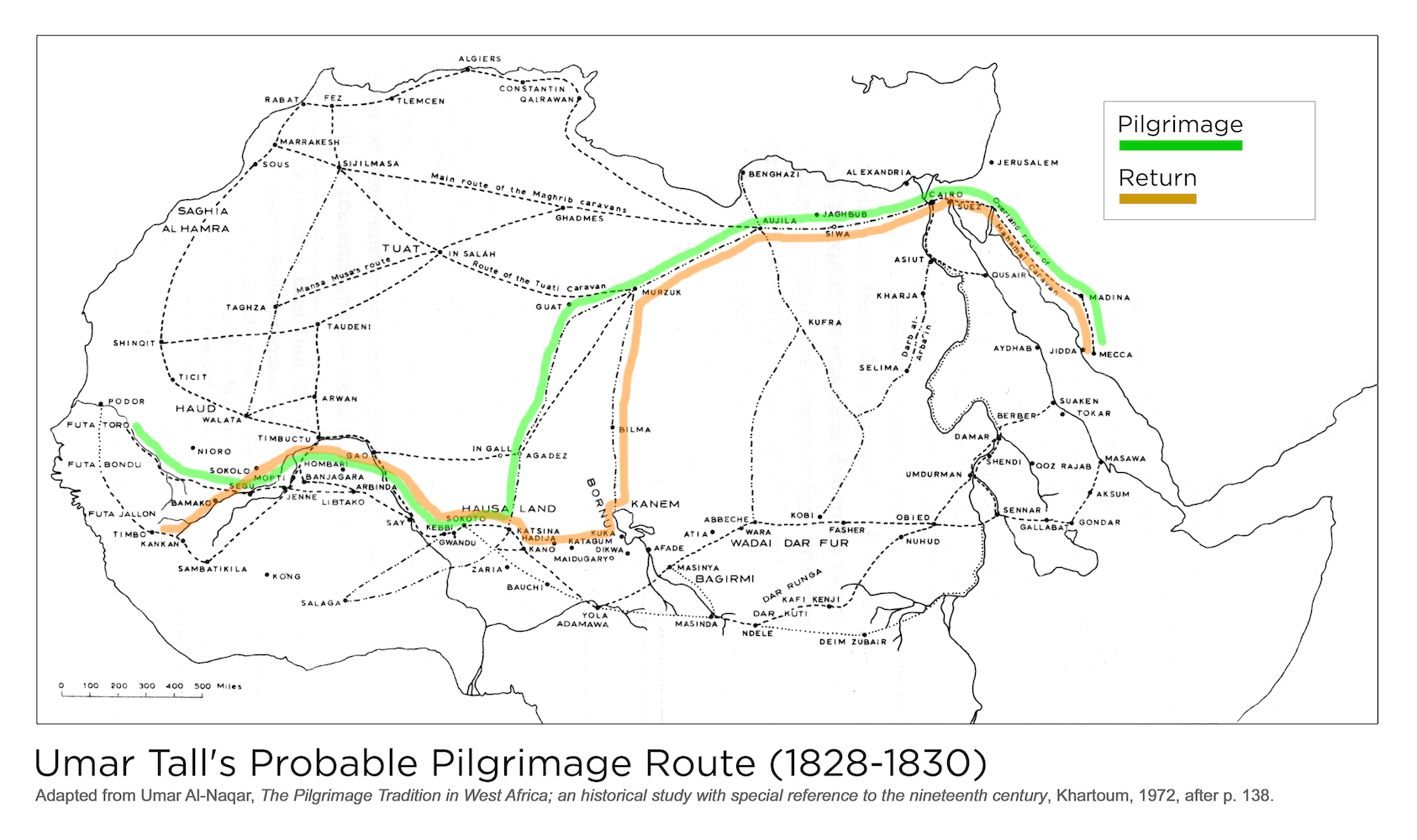

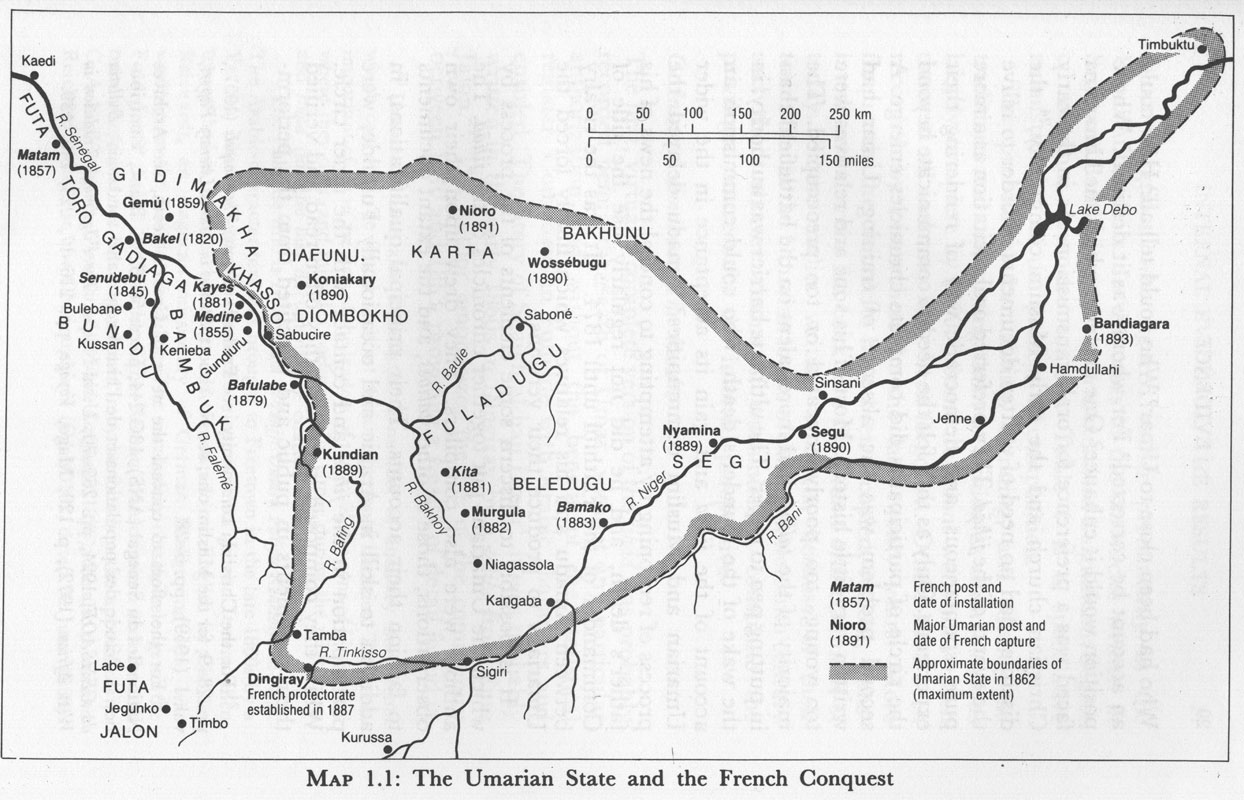

By far the best known of the reformers was Umar Tall ( c.1797-1864). Umar hailed from the village of Halwar, in western Futa Toro. He grew up at a time when the Almamate was already failing as an Islamic venture. He studied with and married into some prestigious Muslim families of the region, then accomplished the overland pilgrimage to Mecca (see embedded map), a highly unusual achievement at the time, and became a leader of islamization in West Africa, particularly in the form of the Tijaniyya Sufi order. He acquired a considerable reputation as a scholar, writer and teacher in the 1840s, from a base in the Almamate of Futa Jalon. He then embarked on a military jihad, framed as a "jihad against 'paganism'", in 1852. He was killed in 1864, at which point a troubled succession began under his oldest son, Ahmad al-Kabir ( c 1834 - 1897), who presided over what the French called "the Tokolor Empire" until they dismantled it in the early 1890s. This gallery will be built around the achievements but also the "troubles" which Umar and his son faced over their careers, troubles that gave a bad odor to the "Islamic state" movements in Senegambia and the wider region. These troubles, or civil wars, are examples of fitna, the Arabic word for disorder within the state and society. Fitna is applied first and foremost to two periods of early Islamic history, periods which gave birth to Shia Islam and the Sunni - Shia conflict.

Umar's Travels and Credentials

Umar became affiliated with the Tijaniyya Sufi order by his twenties, and embarked on an overland pilgrimage in the late 1820s. The embedded map above plots Umar's probable pilgrimage route. This journey, exceptional at the time for someone from West Africa, took him across the Western and Central Sudan and the Sahara. On the way to and from Mecca he visited each of the areas where Islamic states, dominated by Fulbe or Haal-Pulaar people, had already been established: Futa Jalon, in today's Guinea; Masina or the Middle Niger, which went by the name of the Caliphate of Hamdullahi, its capital, in today's Mali; and Sokoto, the capital of the Caliphate of the same name, in the northern Nigeria of today. Sokoto reigned over Hausaland and a wider area, and was the largest and best known of these Islamic regimes. On his return from the Holy Lands in the early 1830s, Umar also stopped in Bornu, an older state on the eastern fringes of the Sokoto regime. Bornu had a strong Islamic identity and a 19th century reform movement, but one that did not go through the "jihad of the sword"; in fact, the Bornu leader al-Kanemi was quite critical of the jihadic movements - especially the Sokoto one which threatened him.

Umar stayed in the Holy Lands and accomplished the pilgrimage in three successive years (1828-30). One of his main purposes was to acquire a more thorough knowledge of the Tijaniyya, at the feet of the order's representative in Medina, the Moroccan Muhammad al-Ghali. When Umar returned to West Africa in the 1830s, he carried the designation as khalifa of the Tijaniyya order for West Africa as well as the title of al-hajj, "pilgrim." Both titles were unusual at the time. They gave Umar considerable distinction wherever he went and threatened some of the more established Muslim interests of his day.

On the return journey the main sojourn was in Sokoto, for about 5 years. He acquired a Tijaniyya following there. He had considerable access to Muhammad Bello, the caliph at the time, and gained invaluable military experience as Sokoto fought with the anciens regimes that had taken refuge to the north, in the confines of today's Niger. The other significant stay was in Hamdullahi, where again his prestige attracted a considerable following and gave birth to a Tijaniyya community. But he also attracted the ire of some members of the ruling lineage as well as the Kunta, Muslim clerics and traders who were based in the north (especially around Timbuktu) and had considerable influence in Masina. The Kunta saw themselves as the dominant authorities on Islamic politics and law in the Western and Central Sudan at the time, and Umar represented a considerable threat.

In several places - and especially in Sokoto - Umar received wives, gifts of the rulers in acknowledgment of his Islamic distinction. This led to an "instant" lineage of Tall, and to considerable competition among wives and sons for the succession, a subject that I return to later. The Umarians, that is the followers of Umar and their descendants, are widely dispersed today across Senegambia, Mauritania, Guinea and Mali, but they all agree on the signal role of their illustrious ancestor and patron. We have no visual images of Umar, but we can offer a verbal image put together from conversations with followers by a French traveler who was in Segu in 1878. Segu was the capital of Umar’s son Ahmad al-Kabir, and Paul Soleillet was on a mission organized by the French government which was operating out of Saint-Louis, a town at the mouth of the Senegal River. It is important to note that Umar died in 1864, and Soleillet was working from the impressions of disciples probably decades earlier. But the portrait is very useful for the personal impact of this important pilgrim, Sufi and military leader who would have such a huge influence in West Africa.

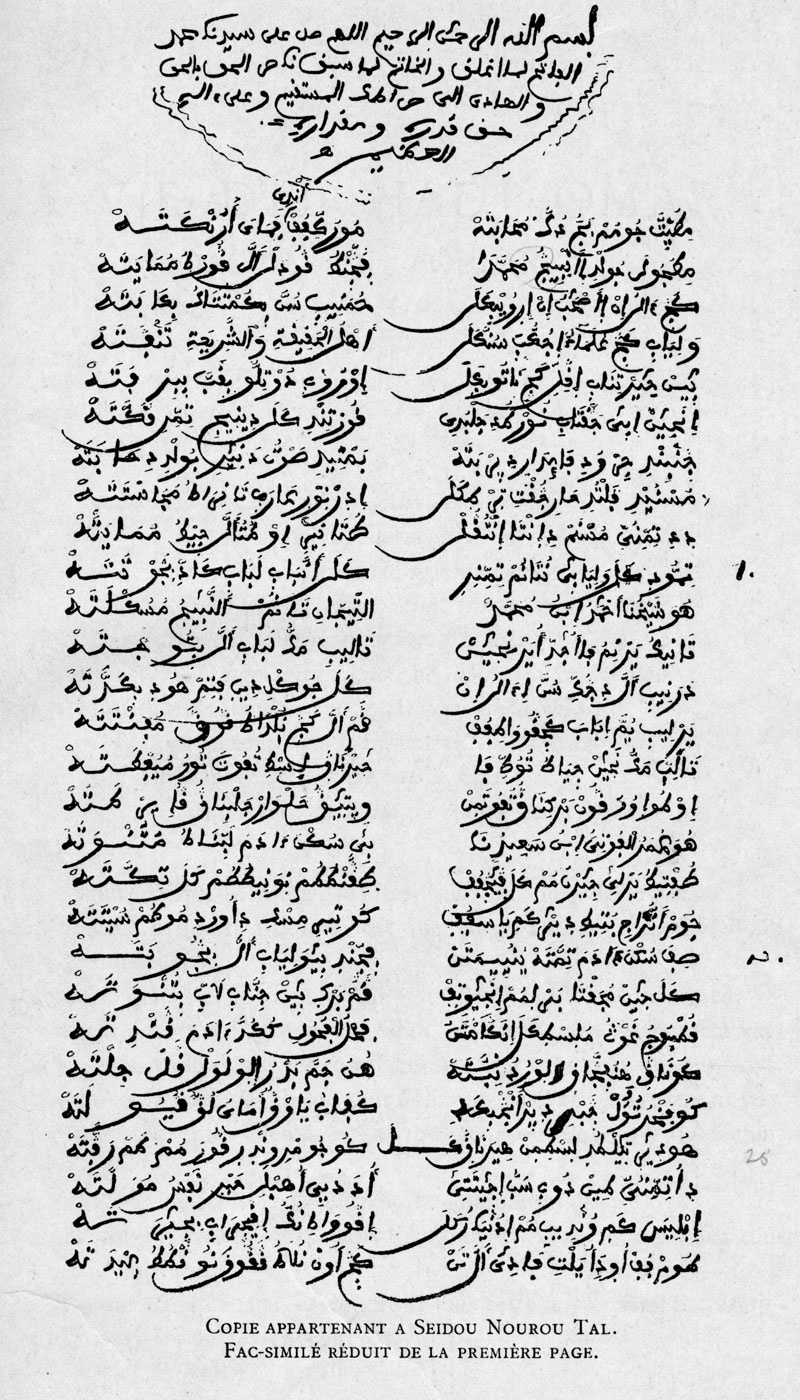

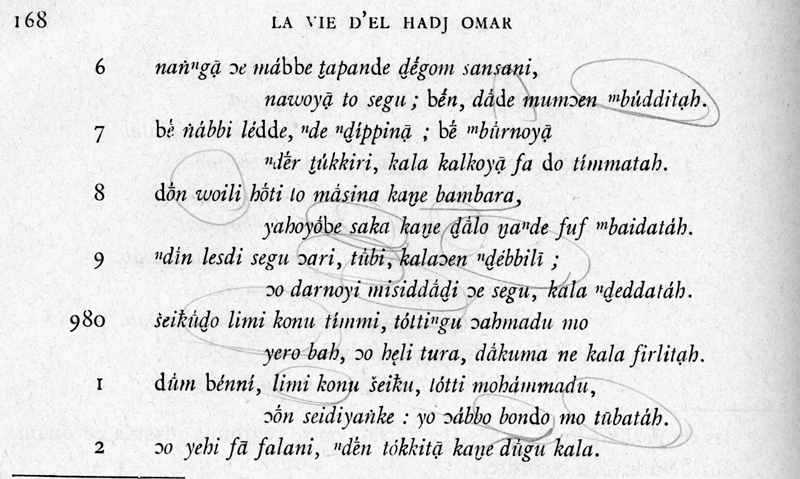

The Umarians were no strangers to writing narrative and hagiography about Umar, and doing it in 'ajami as well as Arabic. 'Ajami, which is the Arabic word for "foreign" or non-Arabic, indicates a text or literature written in the Arabic alphabet but in the local language - in this case Pulaar or Fulfulde. The most elaborate and celebrated 'ajami text of the Umarian enterprise took the form of a Qaçida, or long narrative poem of almost 1200 verses. It was published in 1935 thanks to Henri Gaden, a French military officer, administrator, ethnographer and "pulaarophone" who lived in Saint-Louis, Senegal with his Haal-Pulaar companion. The author was Mohammadou Aliou Tyam, who came from western Futa Toro, not far from Umar's place of birth. Tyam (phonetically Caam) emigrated to the east with other Umarians, settled in Segu, the main capital, and then returned to Futa when the French conquered and began to administer the Sahelian zone of West Africa at the turn of the last century. He wrote, recited and edited his text over a long period of time, and sometime in the early 20th century a copy came into the possession of Gaden, who created a collection of Arabic and `ajami documents which one can still find at the research institute (IFAN) of the Université Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar, under the title "Fonds Gaden."

Gaden edited the Pulaar of Tyam, did a Roman character transliteration, a French interlinear translation, and supplied a commentary, all of which has made the Qaçida an invaluable source for scholars and hagiographers of Umar. What we include here is an excerpt from the beginning of the long poem, to provide the flavor of the text and the way that Umarians view their hero. Tyam invokes blessings on Ahmad al-Tijani, the founder of the Sufi order to which Umar adhered and propagated in West Africa. He stresses the arduous overland pilgrimage, and the two titles important for Umar's later career - first, pilgrim, of course , and, second, the designate (the title usually applied was khalifa, literally "successor") for spreading the Tijaniyya order in West Africa. Here we give the charge which the Tijaniyya representative in Medina gives to Umar as he prepares to return to West Africa - a charge which became the formula for the jihad of "destruction of paganism." A link takes you to the first 14 pages or 75 verses of the poem.

Umar as an Intellectual Leader

On his return from the pilgrimage Al-Hajj Umar, as we can now call him, settled in Futa Jalon, where he had gotten some of his first exposure to the Tijaniyya order. He stayed there for most of the 1840s. Futa Jalon was a hub of economic and religious activity, set at the origins of the main river systems of West Africa: the Niger, the Senegal and the Gambia. Aspiring Muslim students came to its schools from a wide swath of West Africa, from Liberia and Sierra Leone in the south to Senegambia in the north and Mali to the east. Umar was one of these magnets, and he gained widespread prestige as a writer, scholar and Sufi authority. His main work, ar-Rimah, was written during this decade, and summarized his pilgrimage and initiation, his understanding of Islam, and his take on the Tijaniyya order. It is still widely used by leaders of the Tijaniyya today. Had Umar continued this mission, he would certainly be recognized today as one of the great authorities but also the great leaders of islamization in the Western Sudan.

Umar as Leader of the Jihad

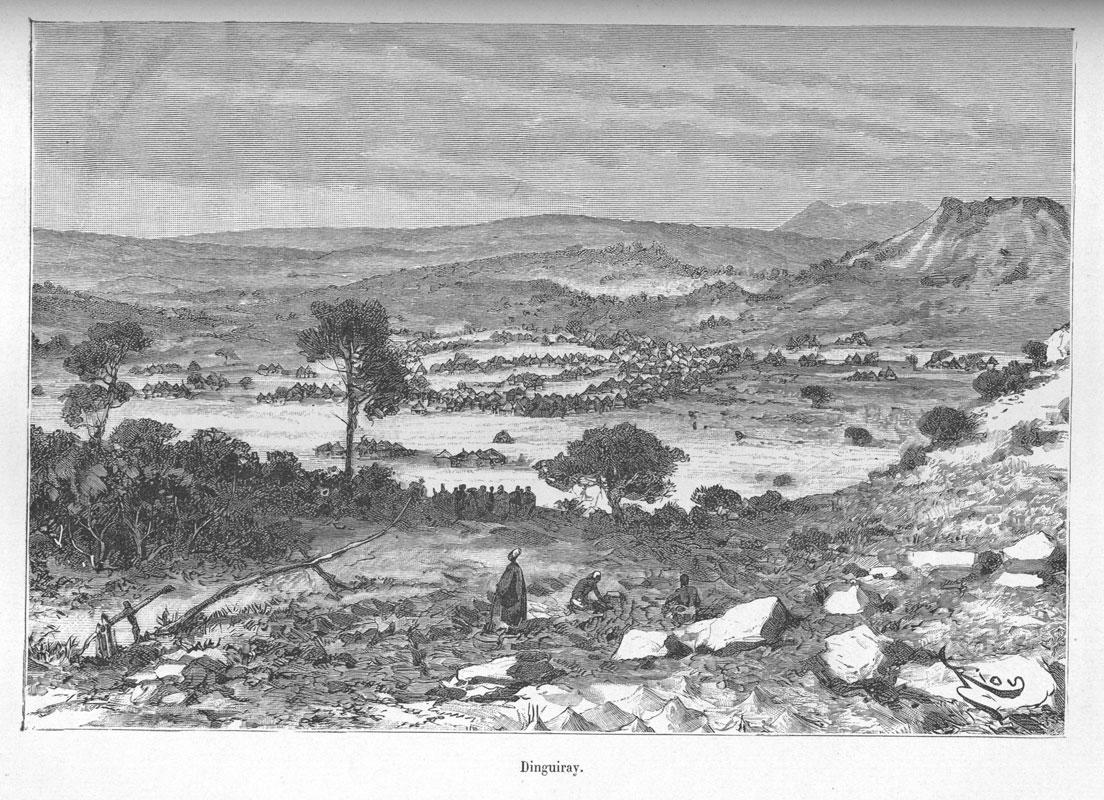

But in the late 1840s Umar began to think of a different mission, of spreading Islam through military means, i.e. waging the "jihad of the sword." This was the main thrust of the reform movements and the main form of Islamic distinction at the time. His shift in mission may have begun with his trip through Senegambia in 1846-7, and the acclaim he received from Muslim minorities and majorities in the different areas. It tied in to the enormous prestige he had acquired in the Holy Lands, unlike the leaders of the previous jihads - including the caliphs of Sokoto. In 1849 Umar took the important step of moving just to the east of Futa Jalon, to a Mandinka kingdom called Tamba, and establishing a new center called Dingiray with the permission of the king. We can consider Dingiray to be the first capital of the Umarians, and the center for the wives, concubines and children of their leader - that is, the "instant" lineage referred to above. Dingiray remained the chief Umarian homestead for several decades, but was gradually overshadowed by the Middle Niger capital of Segu, where Ahmad al-Kabir reigned from the early 1860s to the 1880s.

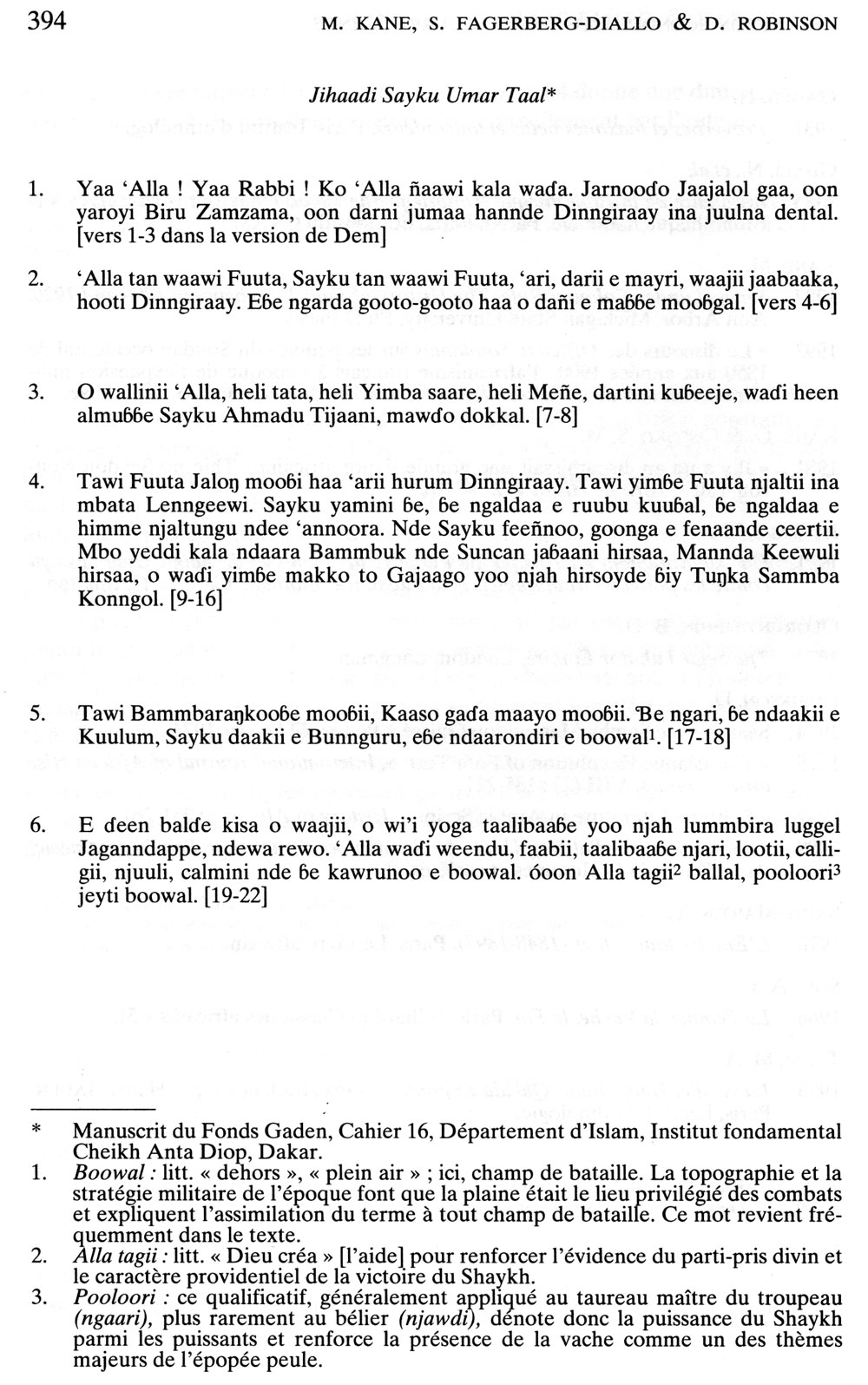

The king of Tamba accepted the new Umarian community but he had the reputation of being resistant if not hostile to Islam. The growing settlement and its increasing militancy produced the predictable conflict and declaration of jihad in 1852. Umar was victorious against Tamba, and he immediately became an important figure in the spread of Islam. He styled himself "the destroyer of paganism," and took on the task of attacking the leading non-Muslim regimes of the day. Tamba was the first, but then he set his sights on two much larger Bambara kingdoms, Kaarta in the northwestern part of today's Mali, and Segu along the Middle Niger. Kaarta had played a role in the downfall of Almamy Abdul Qader of Futa, and it was not difficult to recruit thousands of disciple soldiers in Futa Toro and adjacent areas to wage campaigns, which culminated in the capture of the capital of Nioro in 1855. Segu was a more difficult problem. Stronger militarily than Kaarta, it controlled a considerable portion of the Middle Niger and had significant influence in the West Africa. Umar's recruits embraced his new mission, but they could easily grow weary of the constant campaigning, the violence and loss of life. Rarely did they give voice to their reservations, but below is one example (see Critique of the Umarian... ). It was published only in the 1990s thanks to work with my colleagues, Mamadou Moustapha Kane and Sonja Fagerberg Diallo. It is again an `ajami piece, much shorter than the Qacida, and it came also from the Fonds Gaden, where it had languished for many years. We think this was because it took exception to the dominant positive narrative about the Umarian enterprise. It shows the violence of jihad, for mujahidin as well as "pagans," and the fatigue of war.

Again we present a short excerpt, but with a link to the whole article, where the text appears in Pulaar on one page and English translation on the facing page, with commentary at the bottom. The author is Lamin Maabo Guisse, a griot or oral historian who hailed from western Futa and accompanied Umar on his early military campaigns, and he often addresses himself to the Shaykh, that is to Umar. The excerpt deals in part with the unsuccessful and costly siege of Medine in 1857 (which is described later below).

The Interlude of Conflict with the French

Set between the campaigns against Kaarta and Segu were a series of encounters with the French (1855-60). Under Louis Léon César Faidherbe (Governor of Senegal 1854-61, 1863-5) the French were advancing up the Senegal River, establishing several posts in Futa Toro and the upper Senegal.

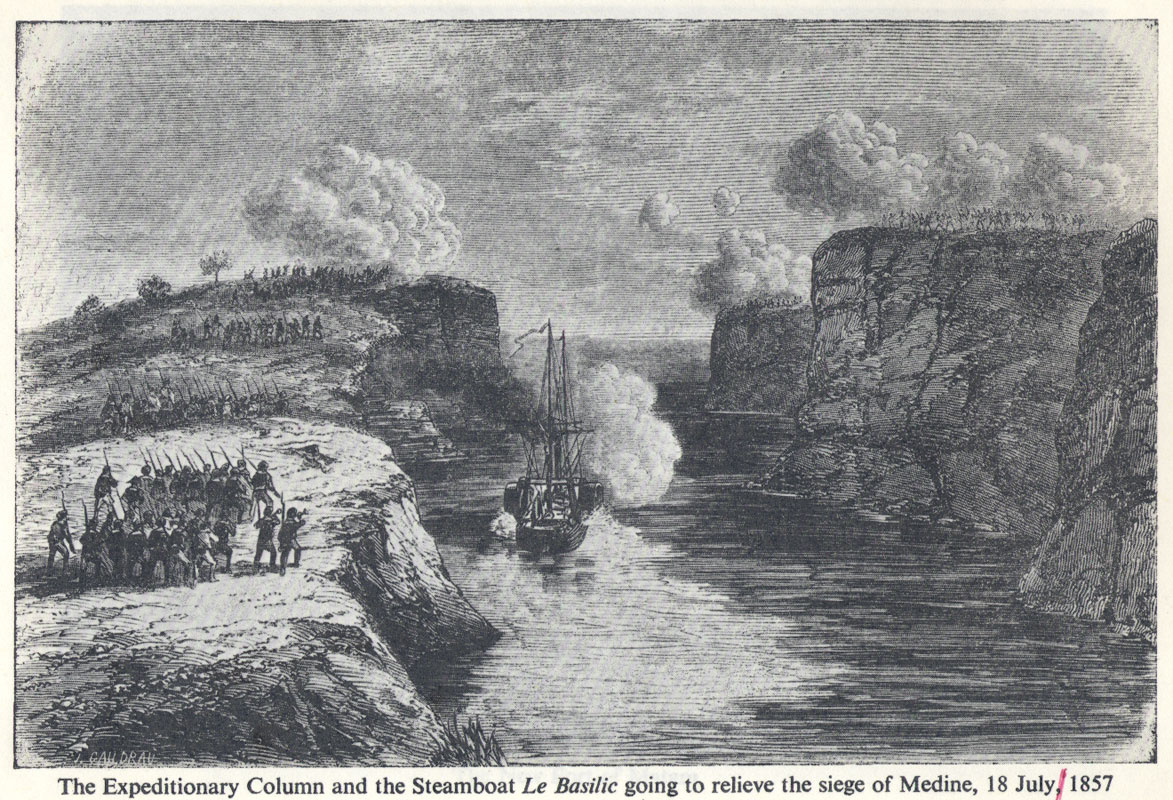

The sharpest clash occurred at Medine, the fort furthest east in present day Mali, in 1857. The mujahidin laid siege to the post at the height of the dry season, and it was only when the rising river allowed Faidherbe to get gunboats and troops to relieve the siege that a stinging defeat for the colonial forces was staved off. Umar recovered and led a massive recruitment drive in Futa Toro in 1858-9, securing the men necessary for his Segu campaign. He stigmatized Futa and most of Senegal as occupied and polluted by the French, who now became the enemies of Islam. The French responded in kind by calling Umar and his community fanatic, anti-Western Muslims. For many it is this conflict, brief but intense, that they remember first when they think of al-hajj Umar.

While the Umarian jihad was directed primarily against the "pagan" enclaves of the Western Sudan, and particularly the Bambara states of Kaarta and Segu, it depended upon recruiting large numbers of Senegalese Muslims to emigrate to the east as members of the Umarian army. This brought Umar's recruiters into Futa Toro and other parts of the Senegal River valley, to enlist Haal-Pulaar and other Muslim soldiers, and brought them into conflict during the period 1855-60 with the French. I estimate that Umar mobilized more than 40,000 people, mainly men, for his wars in the east (see section on Recruitments in Futa Toro and Senegambia).

Governor Faidherbe enjoyed considerable support from Paris in terms of troops, weapons and money. With these resources he began to build the series of small forts along the middle and upper Senegal valley that culminated in Medine. These forts weakened the autonomy of the Almamate of Futa Toro, the primary recruiting ground in the middle valley, and hampered Umar's movements back and forth across the upper valley, as he prepared to move against the Bambara forces in Kaarta (1855) and Segu (1859).

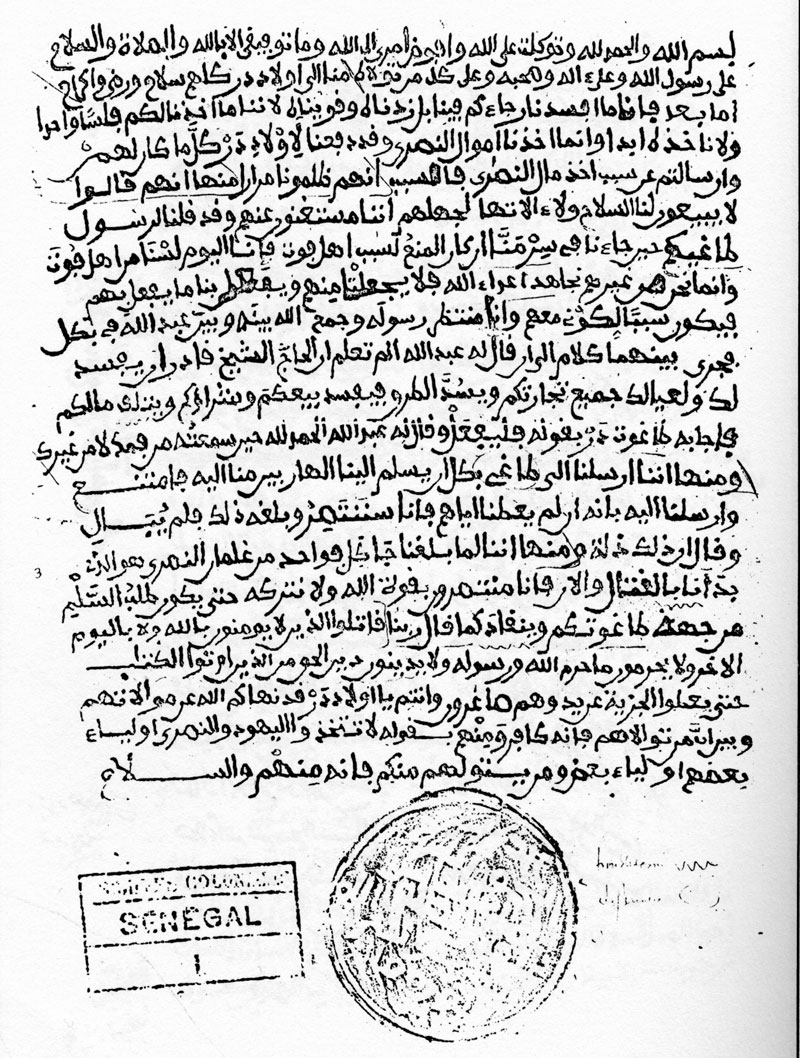

Umar set out his position during this period of conflict in a letter which he wrote in 1855 to the Muslims of Saint-Louis, the French colonial center at the mouth of the river, warning them against collaboration with the "infidel" Europeans. He used the term muwallat, "association," to describe that collaboration and summoned a number of Quranic verses to buttress his argument. He described Faidherbe as "the tyrant," a designation similar to "pharaoh," someone to be opposed. Ndar is the Wolof word for Saint-Louis. Jizya is the tax which non-Muslims pay to the Muslim authority for permission to live and function within the Dar al-Islam.

Umar laid siege to the fort of Medine at the height of the dry season, in April 1857. Medine interfered with the recruitment campaigns he was preparing before attacking Segu. Captain Paul Holle, a mulatto officer from Saint-Louis, managed to resist the onslaught for several months, using the commanding position of the fort above the river, and he became a hero of French imperialism when Faidherbe managed to get upriver and relieve him in July. The narrative of "liberation," reflected in this image, had a big play in French media and understanding at the time - and ever since.

Massive Recruitment in Futa Toro and Senegambia

Umar's failure to take Medine and his determination to march against the formidable Bambara kingdom of Segu intensified his recruitment campaign in 1858-9 in his original homeland. If he wished to continue the "jihad against paganism" against the "arch pagan" regime of Segu, he must recruit massively in Futa Toro, march his men across the vast territory between the Upper Senegal and Middle Niger basins, and organize them into effective fighting units. He confronted the mobilization task head on. His enormous prestige provided substantial security - from indigenous opponents and the French - as he moved downriver to the ceremonial capital of Futa Toro, Hore-Fonde, and made it his base of operations for several months. The "establishment" of the Almamate could not oppose him openly. They argued that Futa was already a Muslim society and that its inhabitants did not need to leave home in order to find "true" Islam. Umar countered their claims by showing the failure to practice Islam fully, the "pollution" which came from "association" with the French, and the greater urgency of the "jihad against paganism" in the east.

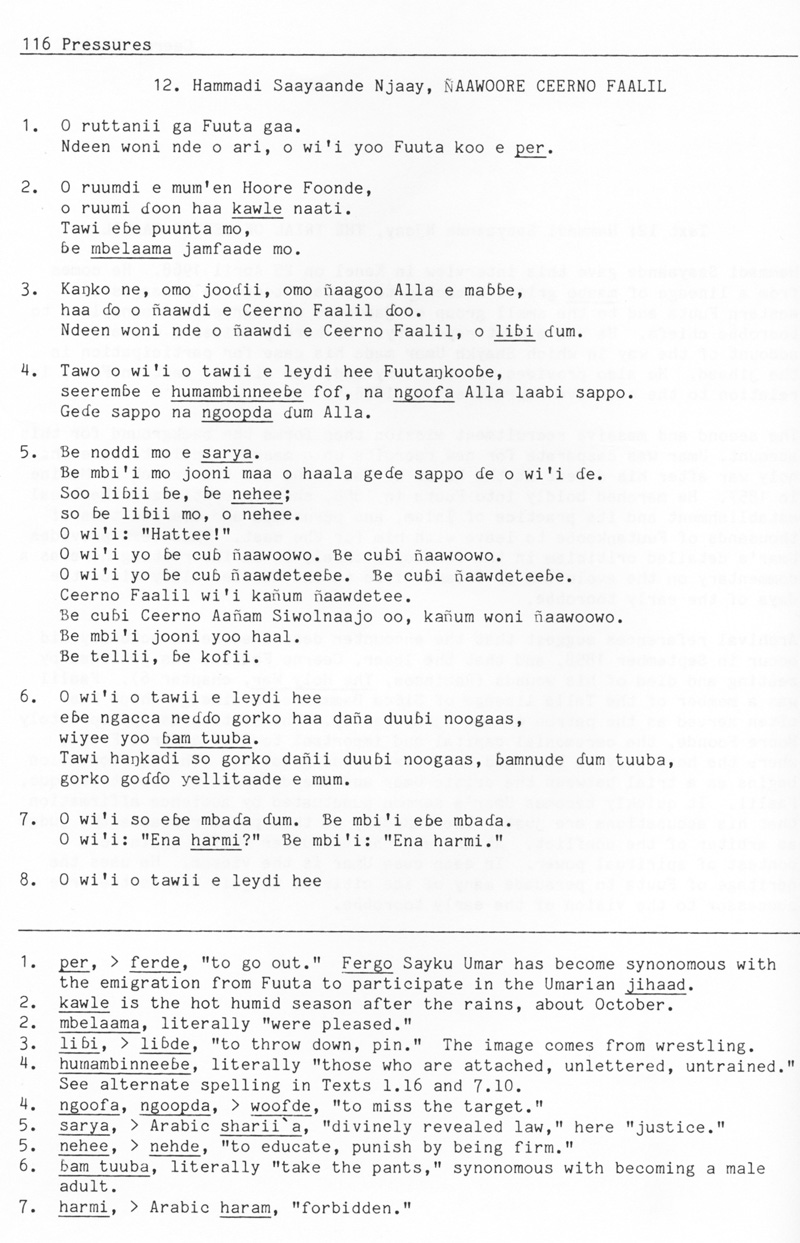

One version of the debate is taken from an interview with an important oral historian of Futa, Hamady Sayande Ndiaye, in the 1960s. It takes the form of a trial between Umar and one of the main leaders of the Almamate, a certain Cerno Falil Talla. It takes place in Hore-Fonde, and the audience serves as a kind of chorus and judge of the positions. A French commandant mentions a similar encounter in the archives, an encounter set in late September 1858. (Full interview can be accessed through the sidebar.)

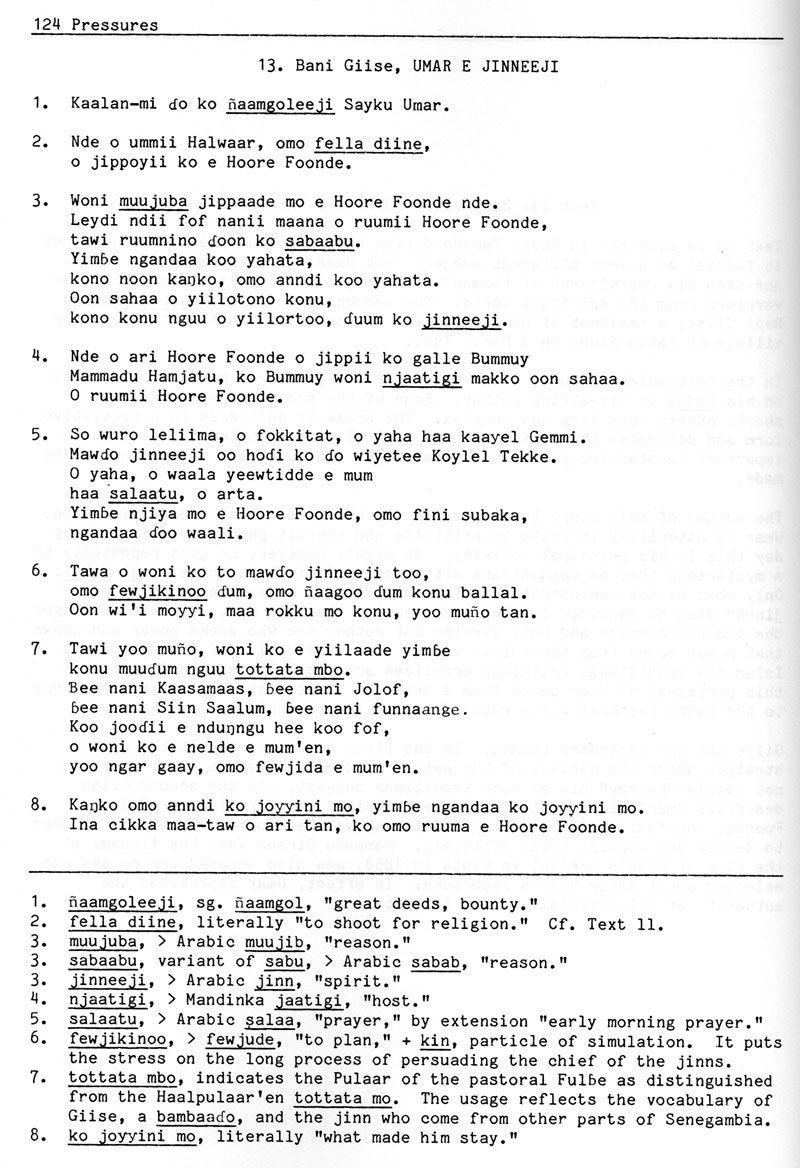

Another story about the encounters of the year in Futa Toro transposes the urgency that Umar faced on to the spiritual terrain, and not the sort that one thinks of as part of Islamic reform. In this session, Bani Giise, a griot affiliated with the more traditional and less Islamic Fulbe groups of Futa Toro, describes the recuitment to the accompaniment of a traditional guitar. Umar goes out into the bush at night and entreats the jinns, spirits, to bring him an army capable of fighting the enemy. By implication the army of jinns will be even stronger than the army of regular soldiers, and make him invincible. (The Pulaar and English version of Bani Giise's interview can be accessed through the sidebar.)

Triumph: the Conquest of Segu

Umar succeeded in his massive recruitment. Against great odds, he conquered the mighty kingdom of Segu in a series of battles between 1859 and 1861. He then entered the capital and the palace of King Ali, who had already fled to the Caliphate of Hamdullahi. He organized a public burning of the "fetishes" of the chief priest and king - as a way of identifying Segu as "pagan" and marking the advent of Islam. The Segu triumph was the culmination of the "jihad against paganism."

Segu had been a powerful force for almost two centuries, extending its influence to the south and the west, with a deep involvement in slavery and the slave trade in several directions. It contained Muslims and non-Muslims of various stripes, and enforced no particular religion, but its ruling class adhered to traditional Bambara customs. For Umar and other Muslims this was paganism, indeed arch paganism, and must be eliminated as the Western Sudan became a "land of Islam." This was the mission which Umar, pilgrim and leader of the Tijaniyya, now leader of the jihad, had given himself. The victories were a remarkable achievement for an army recruited hundreds of miles away and facing an enemy with a ferocious reputation. Muslim authorities from as far away as North Africa sent Umar their congratulations.

We have chosen two excerpts to show the importance of these events. The first, which we can call an internal source and label Triumph over paganism at Segu, comes from the same source used in the Praise poem of Umar Tall, that is the 'ajami poetry of Mohammadou Aliou Tyam, and it describes Umar's entry into the Bambara capital and palace. Umar is called the Differentiator, farugu, an echo of his name sake who was the second caliph after Muhammad. Like Caliph Umar, Shaykh Umar could differentiate between good and evil, Muslim and pagan, devout and hypocritical. He keeps the idols or "festishes" of Segu to serve as proof of the religious identity of the ruling class in his growing dispute with Masina and the Kunta (see below).

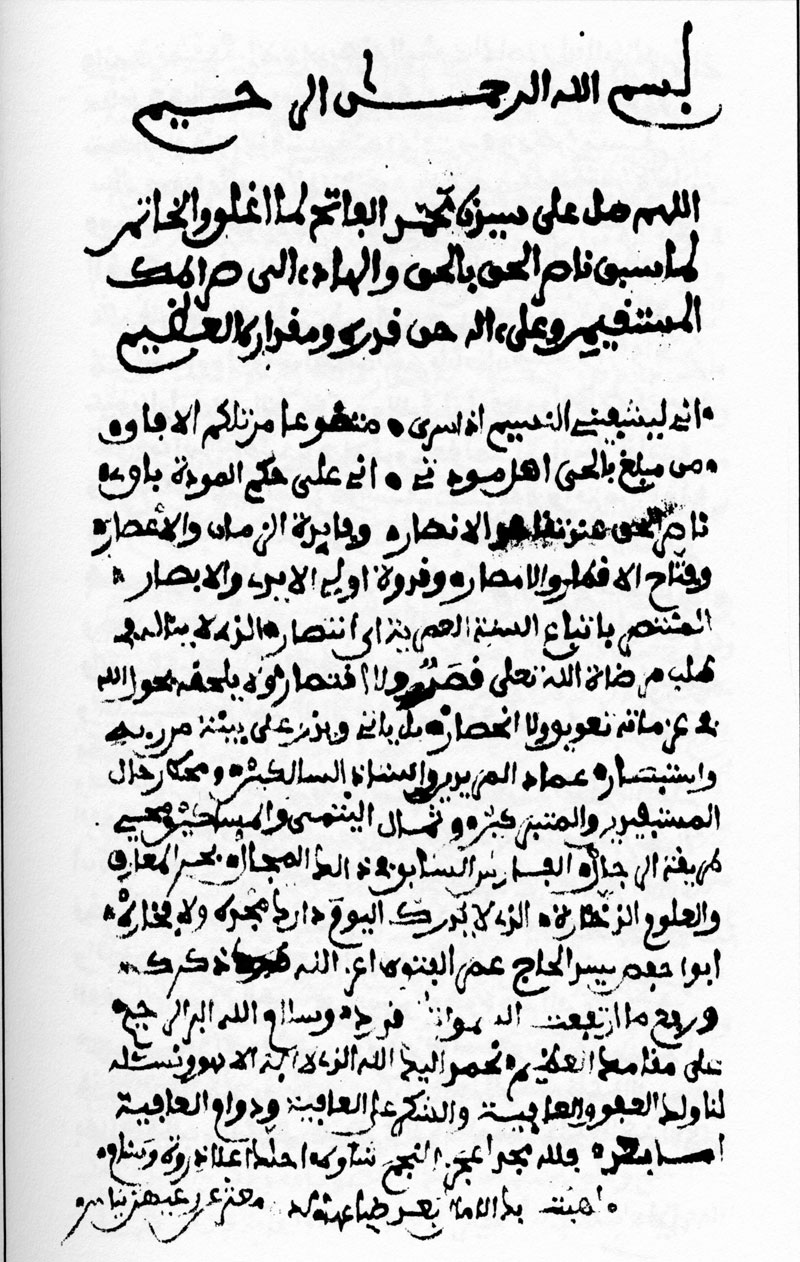

The second text, which we can call an external opinion, constitutes Congratulations from Morocco. It comes from a congratulatory letter sent to Umar from Morocco. Ahmad al-Tijani, the founder of the Tijaniyya Sufi order in Algeria, migrated to Fez, the intellectual capital of Morocco, in the late 18th century. He was buried in the city, whereupon his tomb became a place of pilgrimage for Tijani Sufis from all over Africa. The order became important in Morocco, at the court and in the cities. In the mid-19th century its leading figure was Muhammad al-Kansusi, who carried on an energetic epistolary debate with Ahmad al-Bakkay and other Kunta, partisans of the older, more established Qadiriyya order. From his base in Marrakesh, al-Kansusi followed closely the fortunes of Al-hajj Umar, as the leader of the new Tijaniyya allegiance in West Africa. Letters traveled rapidly between the Western Sudan and Morocco, and al-Kansusi learned of Umar’s triumph over the Bambara army at the critical battle of Woitala in 1860, months before the triumphant entry into Segu. He dashed off a note of congratulation which has a prominent place in the Umarian memory and archives. The note shows that victory over the Bambara of Segu, and the removal of this obstacle to islamisation, was the culmination of the Umarian "destruction of paganism."

Therefore we thank God who, through you, has removed obstacles, and helped to spread your message, and through your happy rule set in order what was confused and destroyed the evil people. Be happy, O master in the bounty of God. May your days be happy with God’s happiness....

We have written this on the fifth of Rabi` II in the year 1277 AH [21 October 1860].

The Jihad that Became Fitna

As we have said, Umar's emphasis throughout the "jihadic period" was not resistance to the Europeans but the "destruction of paganism" in the Western Sudan. Or at least it was until he conquered Segu in 1861, and discovered fully the complicity of the Hamdullahi regime and the Kunta Muslim network in the support of Segu against the Umarian jihad.

From the time of his campaigns against Kaarta in 1855, Umar became aware of the opposition of Hamdullahi, now led by a young caliph Amadu mo Amadu. Masina sent an occasional army to slow Umar's advance, and by the late 1850s prepared a more concerted resistance, in conjunction with the Kunta and their leader, Ahmad al-Bakkay. This resistance included an arrangement for the conversion of the Segu king to Islam. On this basis Hamdullahi and the Kunta could claim that Segu was now Muslim and not a suitable target of the Umarian jihad.

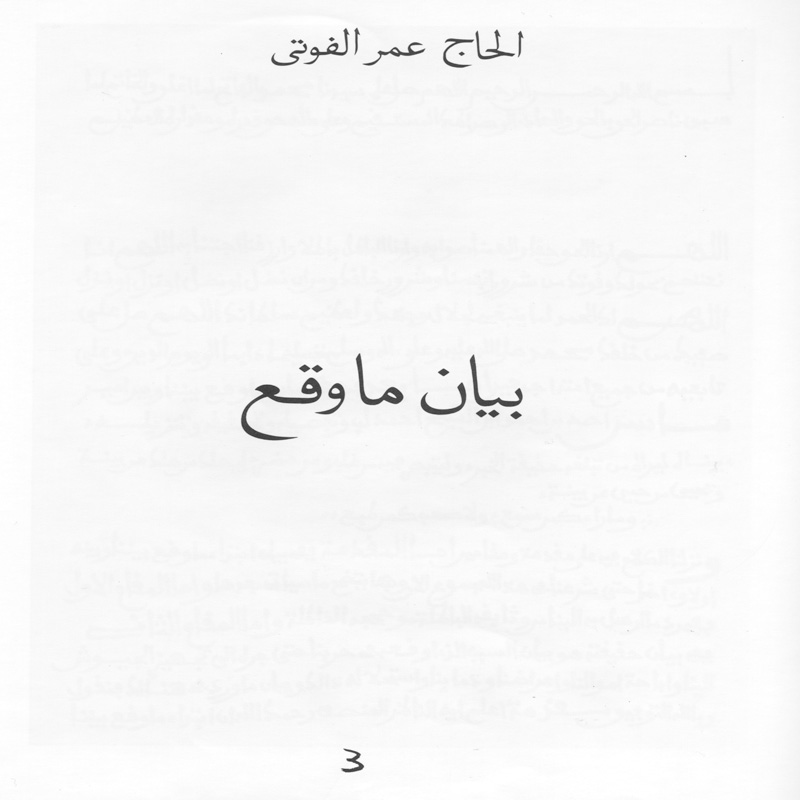

Umar discovered in the palace of King Ali a considerable correspondence between Ahmad al-Bakkay, Amado mo Amadu and the Segu king. This proved his contention about the complicity of these ostensibly good Muslim leaders - the Fulbe caliph in Hamdullahi and the Kunta scholar in Timbuktu - with an obviously pagan ruler of the Western Sudan. Umar was furious, and spent the next year corresponding with Hamdullahi, demanding an apology and the surrender of King Ali, and composing a text which showed the complicity and how it contradicted the norms of Islam. He went so far as to invoke the concept of takfir, "excommunication" or apostasy, and applied it to the caliph and his court. This meant that in his eyes Hamdullahi was no longer Muslim, in which case it was a suitable candidate for jihad. The document, bristling with references to the Quran and Muslim authorities over the centuries, was called the Bayan Ma Waqa`a d’al hajj Umar, and served as a justification for the military campaign against Masina launched in 1862. Here we take brief excerpts from the very last part of the Bayan; Umar is summarizing his points against the caliph.

When Hamdullahi refused the apology and the surrender of the king, Umar mobilized most of his army and embarked on a campaign against Hamdullahi. The campaign pitted Fulbe Muslim reformer against Fulbe Muslim reformer, and provoked great controversy among Muslim communities across West Africa. I have called this the first fitna of the Umarian movement. What were the results of the campaign? Initial victory in 1862, against both Hamdullahi and Timbuktu. During that year one might have said that Umar was on the verge of creating an Islamic regime in the Western Sudan comparable to the one Sokoto dominated in the Central Sudan. We have included here a map showing the areas conquered by Umar by 1862; he did not establish control of those areas, however, before "things began to fall apart."

But things rapidly fell apart, beginning with the defeat of the main Umarian army near Timbuktu and a revolt and siege of the Umarian forces in Hamdullahi itself. Early in 1864 Umar and a handful of supporters escaped to the cliffs of Degembere to the east, but there they succumbed to the Masinanke pursuit. Umar's nephew, Ahmad al-Tijani, did survive, and from his center in Bandiagara managed to resume the recapture of Masina - at great cost in lives and livelihood - over the next 25 years.

I have called the whole attack, revolt and recapture the first fitna of the Umarian movement. Fitna means struggle or civil war, and it is the term which the early Muslim community of the Arabian peninsula used to describe the conflicts which resulted in the division between Sunni and Shia Islam. The Umarian-Masinanke struggle put Muslim authorities throughout the Western Sudan in a very awkward situation: here two Muslim Fulbe regimes, both ostensibly reform-minded, were pitted against each other. The campaign to "destroy paganism" was forgotten, as well as the mission to spread the practice of Islam. And it left Umar's oldest son and successor, Ahmad al-Kabir, with a huge set of problems.

Umar's Travels and Credentials

Umar became affiliated with the Tijaniyya Sufi order by his twenties, and embarked on an overland pilgrimage in the late 1820s. The embedded map above plots Umar's probable pilgrimage route. This journey, exceptional at the time for someone from West Africa, took him across the Western and Central Sudan and the Sahara. On the way to and from Mecca he visited each of the areas where Islamic states, dominated by Fulbe or Haal-Pulaar people, had already been established: Futa Jalon, in today's Guinea; Masina or the Middle Niger, which went by the name of the Caliphate of Hamdullahi, its capital, in today's Mali; and Sokoto, the capital of the Caliphate of the same name, in the northern Nigeria of today. Sokoto reigned over Hausaland and a wider area, and was the largest and best known of these Islamic regimes. On his return from the Holy Lands in the early 1830s, Umar also stopped in Bornu, an older state on the eastern fringes of the Sokoto regime. Bornu had a strong Islamic identity and a 19th century reform movement, but one that did not go through the "jihad of the sword"; in fact, the Bornu leader al-Kanemi was quite critical of the jihadic movements - especially the Sokoto one which threatened him.

Umar stayed in the Holy Lands and accomplished the pilgrimage in three successive years (1828-30). One of his main purposes was to acquire a more thorough knowledge of the Tijaniyya, at the feet of the order's representative in Medina, the Moroccan Muhammad al-Ghali. When Umar returned to West Africa in the 1830s, he carried the designation as khalifa of the Tijaniyya order for West Africa as well as the title of al-hajj, "pilgrim." Both titles were unusual at the time. They gave Umar considerable distinction wherever he went and threatened some of the more established Muslim interests of his day.

On the return journey the main sojourn was in Sokoto, for about 5 years. He acquired a Tijaniyya following there. He had considerable access to Muhammad Bello, the caliph at the time, and gained invaluable military experience as Sokoto fought with the anciens regimes that had taken refuge to the north, in the confines of today's Niger. The other significant stay was in Hamdullahi, where again his prestige attracted a considerable following and gave birth to a Tijaniyya community. But he also attracted the ire of some members of the ruling lineage as well as the Kunta, Muslim clerics and traders who were based in the north (especially around Timbuktu) and had considerable influence in Masina. The Kunta saw themselves as the dominant authorities on Islamic politics and law in the Western and Central Sudan at the time, and Umar represented a considerable threat.

In several places - and especially in Sokoto - Umar received wives, gifts of the rulers in acknowledgment of his Islamic distinction. This led to an "instant" lineage of Tall, and to considerable competition among wives and sons for the succession, a subject that I return to later. The Umarians, that is the followers of Umar and their descendants, are widely dispersed today across Senegambia, Mauritania, Guinea and Mali, but they all agree on the signal role of their illustrious ancestor and patron. We have no visual images of Umar, but we can offer a verbal image put together from conversations with followers by a French traveler who was in Segu in 1878. Segu was the capital of Umar’s son Ahmad al-Kabir, and Paul Soleillet was on a mission organized by the French government which was operating out of Saint-Louis, a town at the mouth of the Senegal River. It is important to note that Umar died in 1864, and Soleillet was working from the impressions of disciples probably decades earlier. But the portrait is very useful for the personal impact of this important pilgrim, Sufi and military leader who would have such a huge influence in West Africa.

Verbal portrait of Umar

The Shaikh was always simply clothed: a small calico cap, short turban, white shirt and pants covered with a light blue robe, and yellow slippers.... In his hand he carried a small metal pot and, on important occasions, one of his two canes.... He was strikingly handsome. His eyes were clear; his skin bronzed, his features symmetrical. His beard was black, long, soft and divided at the chin. He wore no mustache.

He seemed never to be more than thirty years old. No one ever saw him blow his nose, spit, sweat or complain of being warm or cold. He could go indefinitely without eating or drinking. He never seemed to tire of riding, walking, or remaining seated on a mat.

His voice was gentle, but it had extraordinary carrying quality. He never laughed nor cried, he never got angry. His face was always calm and smiling....

The Shaikh was always simply clothed: a small calico cap, short turban, white shirt and pants covered with a light blue robe, and yellow slippers.... In his hand he carried a small metal pot and, on important occasions, one of his two canes.... He was strikingly handsome. His eyes were clear; his skin bronzed, his features symmetrical. His beard was black, long, soft and divided at the chin. He wore no mustache.

He seemed never to be more than thirty years old. No one ever saw him blow his nose, spit, sweat or complain of being warm or cold. He could go indefinitely without eating or drinking. He never seemed to tire of riding, walking, or remaining seated on a mat.

His voice was gentle, but it had extraordinary carrying quality. He never laughed nor cried, he never got angry. His face was always calm and smiling....

The Umarians were no strangers to writing narrative and hagiography about Umar, and doing it in 'ajami as well as Arabic. 'Ajami, which is the Arabic word for "foreign" or non-Arabic, indicates a text or literature written in the Arabic alphabet but in the local language - in this case Pulaar or Fulfulde. The most elaborate and celebrated 'ajami text of the Umarian enterprise took the form of a Qaçida, or long narrative poem of almost 1200 verses. It was published in 1935 thanks to Henri Gaden, a French military officer, administrator, ethnographer and "pulaarophone" who lived in Saint-Louis, Senegal with his Haal-Pulaar companion. The author was Mohammadou Aliou Tyam, who came from western Futa Toro, not far from Umar's place of birth. Tyam (phonetically Caam) emigrated to the east with other Umarians, settled in Segu, the main capital, and then returned to Futa when the French conquered and began to administer the Sahelian zone of West Africa at the turn of the last century. He wrote, recited and edited his text over a long period of time, and sometime in the early 20th century a copy came into the possession of Gaden, who created a collection of Arabic and `ajami documents which one can still find at the research institute (IFAN) of the Université Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar, under the title "Fonds Gaden."

Gaden edited the Pulaar of Tyam, did a Roman character transliteration, a French interlinear translation, and supplied a commentary, all of which has made the Qaçida an invaluable source for scholars and hagiographers of Umar. What we include here is an excerpt from the beginning of the long poem, to provide the flavor of the text and the way that Umarians view their hero. Tyam invokes blessings on Ahmad al-Tijani, the founder of the Sufi order to which Umar adhered and propagated in West Africa. He stresses the arduous overland pilgrimage, and the two titles important for Umar's later career - first, pilgrim, of course , and, second, the designate (the title usually applied was khalifa, literally "successor") for spreading the Tijaniyya order in West Africa. Here we give the charge which the Tijaniyya representative in Medina gives to Umar as he prepares to return to West Africa - a charge which became the formula for the jihad of "destruction of paganism." A link takes you to the first 14 pages or 75 verses of the poem.

Praise poem of Umar’s career in `ajami

Verse 70 ...Then he ordered him to return to the West: "Go sweep out the country," [said] the superior one who does not tire out:

71 "All affairs of this world and the other, all are in your hands. You, my disciple, listen and remember:

72 Do not associate yourself with the kings of this world and their companions, listen so as to understand well."

Verse 70 ...Then he ordered him to return to the West: "Go sweep out the country," [said] the superior one who does not tire out:

71 "All affairs of this world and the other, all are in your hands. You, my disciple, listen and remember:

72 Do not associate yourself with the kings of this world and their companions, listen so as to understand well."

Umar as an Intellectual Leader

On his return from the pilgrimage Al-Hajj Umar, as we can now call him, settled in Futa Jalon, where he had gotten some of his first exposure to the Tijaniyya order. He stayed there for most of the 1840s. Futa Jalon was a hub of economic and religious activity, set at the origins of the main river systems of West Africa: the Niger, the Senegal and the Gambia. Aspiring Muslim students came to its schools from a wide swath of West Africa, from Liberia and Sierra Leone in the south to Senegambia in the north and Mali to the east. Umar was one of these magnets, and he gained widespread prestige as a writer, scholar and Sufi authority. His main work, ar-Rimah, was written during this decade, and summarized his pilgrimage and initiation, his understanding of Islam, and his take on the Tijaniyya order. It is still widely used by leaders of the Tijaniyya today. Had Umar continued this mission, he would certainly be recognized today as one of the great authorities but also the great leaders of islamization in the Western Sudan.

Umar as Leader of the Jihad

But in the late 1840s Umar began to think of a different mission, of spreading Islam through military means, i.e. waging the "jihad of the sword." This was the main thrust of the reform movements and the main form of Islamic distinction at the time. His shift in mission may have begun with his trip through Senegambia in 1846-7, and the acclaim he received from Muslim minorities and majorities in the different areas. It tied in to the enormous prestige he had acquired in the Holy Lands, unlike the leaders of the previous jihads - including the caliphs of Sokoto. In 1849 Umar took the important step of moving just to the east of Futa Jalon, to a Mandinka kingdom called Tamba, and establishing a new center called Dingiray with the permission of the king. We can consider Dingiray to be the first capital of the Umarians, and the center for the wives, concubines and children of their leader - that is, the "instant" lineage referred to above. Dingiray remained the chief Umarian homestead for several decades, but was gradually overshadowed by the Middle Niger capital of Segu, where Ahmad al-Kabir reigned from the early 1860s to the 1880s.

The king of Tamba accepted the new Umarian community but he had the reputation of being resistant if not hostile to Islam. The growing settlement and its increasing militancy produced the predictable conflict and declaration of jihad in 1852. Umar was victorious against Tamba, and he immediately became an important figure in the spread of Islam. He styled himself "the destroyer of paganism," and took on the task of attacking the leading non-Muslim regimes of the day. Tamba was the first, but then he set his sights on two much larger Bambara kingdoms, Kaarta in the northwestern part of today's Mali, and Segu along the Middle Niger. Kaarta had played a role in the downfall of Almamy Abdul Qader of Futa, and it was not difficult to recruit thousands of disciple soldiers in Futa Toro and adjacent areas to wage campaigns, which culminated in the capture of the capital of Nioro in 1855. Segu was a more difficult problem. Stronger militarily than Kaarta, it controlled a considerable portion of the Middle Niger and had significant influence in the West Africa. Umar's recruits embraced his new mission, but they could easily grow weary of the constant campaigning, the violence and loss of life. Rarely did they give voice to their reservations, but below is one example (see Critique of the Umarian... ). It was published only in the 1990s thanks to work with my colleagues, Mamadou Moustapha Kane and Sonja Fagerberg Diallo. It is again an `ajami piece, much shorter than the Qacida, and it came also from the Fonds Gaden, where it had languished for many years. We think this was because it took exception to the dominant positive narrative about the Umarian enterprise. It shows the violence of jihad, for mujahidin as well as "pagans," and the fatigue of war.

Again we present a short excerpt, but with a link to the whole article, where the text appears in Pulaar on one page and English translation on the facing page, with commentary at the bottom. The author is Lamin Maabo Guisse, a griot or oral historian who hailed from western Futa and accompanied Umar on his early military campaigns, and he often addresses himself to the Shaykh, that is to Umar. The excerpt deals in part with the unsuccessful and costly siege of Medine in 1857 (which is described later below).

An ajami critique of the jihad of Umar Tall

Verse 79. Oh how the sons of Futa perished at the siege of Medine, ...a whole row of my companions lay on the ground beside the trench,

80. God is my witness, my dear Shaykh, not one [of the dead] was killed by a bullet in the back. The clothes were everywhere on the field of the dead, and the widows [back in Futa] were legion....

83. Have mercy, my dear Shaykh, let us return home quickly so that, by God, the seed for sowing will be saved. See, sons of Futa, the birds swooping to tellus that the floodplain is ready to be cultivated....

84. Have mercy, Shaykh Umar, let us return home! You have defeated the Bambara, you have prevented me from returning home to revive my spirit....

Verse 79. Oh how the sons of Futa perished at the siege of Medine, ...a whole row of my companions lay on the ground beside the trench,

80. God is my witness, my dear Shaykh, not one [of the dead] was killed by a bullet in the back. The clothes were everywhere on the field of the dead, and the widows [back in Futa] were legion....

83. Have mercy, my dear Shaykh, let us return home quickly so that, by God, the seed for sowing will be saved. See, sons of Futa, the birds swooping to tellus that the floodplain is ready to be cultivated....

84. Have mercy, Shaykh Umar, let us return home! You have defeated the Bambara, you have prevented me from returning home to revive my spirit....

The Interlude of Conflict with the French

Set between the campaigns against Kaarta and Segu were a series of encounters with the French (1855-60). Under Louis Léon César Faidherbe (Governor of Senegal 1854-61, 1863-5) the French were advancing up the Senegal River, establishing several posts in Futa Toro and the upper Senegal.

The sharpest clash occurred at Medine, the fort furthest east in present day Mali, in 1857. The mujahidin laid siege to the post at the height of the dry season, and it was only when the rising river allowed Faidherbe to get gunboats and troops to relieve the siege that a stinging defeat for the colonial forces was staved off. Umar recovered and led a massive recruitment drive in Futa Toro in 1858-9, securing the men necessary for his Segu campaign. He stigmatized Futa and most of Senegal as occupied and polluted by the French, who now became the enemies of Islam. The French responded in kind by calling Umar and his community fanatic, anti-Western Muslims. For many it is this conflict, brief but intense, that they remember first when they think of al-hajj Umar.

While the Umarian jihad was directed primarily against the "pagan" enclaves of the Western Sudan, and particularly the Bambara states of Kaarta and Segu, it depended upon recruiting large numbers of Senegalese Muslims to emigrate to the east as members of the Umarian army. This brought Umar's recruiters into Futa Toro and other parts of the Senegal River valley, to enlist Haal-Pulaar and other Muslim soldiers, and brought them into conflict during the period 1855-60 with the French. I estimate that Umar mobilized more than 40,000 people, mainly men, for his wars in the east (see section on Recruitments in Futa Toro and Senegambia).

Governor Faidherbe enjoyed considerable support from Paris in terms of troops, weapons and money. With these resources he began to build the series of small forts along the middle and upper Senegal valley that culminated in Medine. These forts weakened the autonomy of the Almamate of Futa Toro, the primary recruiting ground in the middle valley, and hampered Umar's movements back and forth across the upper valley, as he prepared to move against the Bambara forces in Kaarta (1855) and Segu (1859).

Umar set out his position during this period of conflict in a letter which he wrote in 1855 to the Muslims of Saint-Louis, the French colonial center at the mouth of the river, warning them against collaboration with the "infidel" Europeans. He used the term muwallat, "association," to describe that collaboration and summoned a number of Quranic verses to buttress his argument. He described Faidherbe as "the tyrant," a designation similar to "pharaoh," someone to be opposed. Ndar is the Wolof word for Saint-Louis. Jizya is the tax which non-Muslims pay to the Muslim authority for permission to live and function within the Dar al-Islam.

Warning to Muslims associated with French colonial rule (1855)

From us to all the sons of Ndar. Greetings, good will and honor [be with you]. We have not destroyed your hope in us but rather increased and strengthened it, because we have not taken what belonged to you, not one coin, and we never will. Instead, we have taken the possessions of the Christians. We have returned to the sons of Ndar everything that belonged to them. If you ask the reason for the seizure of the Christian property, it is because they have committed injustices against us many times....

Now we are victorious by the power of God. We will not quit until we receive a plea of peace and submission from your tyrant, for our Lord said: "Fight those who believe not in God nor in the Last Day, nor forbid that which God and His Messenger have forbidden nor follow the religion of truth, out of those who have been given the book, until they pay the jizya in acknowledgment of superiority, for they are in a state of subjection." Sons of Ndar, God forbids you to be in relations of friendship with them. He made it clear that whomever becomes their friend becomes an infidel, and one of them, through His saying: "Take not the Jews and Christians for friends. They are friends of each other. And whomever amongst you takes them for friends he is indeed one of them." Greetings.

From us to all the sons of Ndar. Greetings, good will and honor [be with you]. We have not destroyed your hope in us but rather increased and strengthened it, because we have not taken what belonged to you, not one coin, and we never will. Instead, we have taken the possessions of the Christians. We have returned to the sons of Ndar everything that belonged to them. If you ask the reason for the seizure of the Christian property, it is because they have committed injustices against us many times....

Now we are victorious by the power of God. We will not quit until we receive a plea of peace and submission from your tyrant, for our Lord said: "Fight those who believe not in God nor in the Last Day, nor forbid that which God and His Messenger have forbidden nor follow the religion of truth, out of those who have been given the book, until they pay the jizya in acknowledgment of superiority, for they are in a state of subjection." Sons of Ndar, God forbids you to be in relations of friendship with them. He made it clear that whomever becomes their friend becomes an infidel, and one of them, through His saying: "Take not the Jews and Christians for friends. They are friends of each other. And whomever amongst you takes them for friends he is indeed one of them." Greetings.

Umar laid siege to the fort of Medine at the height of the dry season, in April 1857. Medine interfered with the recruitment campaigns he was preparing before attacking Segu. Captain Paul Holle, a mulatto officer from Saint-Louis, managed to resist the onslaught for several months, using the commanding position of the fort above the river, and he became a hero of French imperialism when Faidherbe managed to get upriver and relieve him in July. The narrative of "liberation," reflected in this image, had a big play in French media and understanding at the time - and ever since.

Massive Recruitment in Futa Toro and Senegambia

Umar's failure to take Medine and his determination to march against the formidable Bambara kingdom of Segu intensified his recruitment campaign in 1858-9 in his original homeland. If he wished to continue the "jihad against paganism" against the "arch pagan" regime of Segu, he must recruit massively in Futa Toro, march his men across the vast territory between the Upper Senegal and Middle Niger basins, and organize them into effective fighting units. He confronted the mobilization task head on. His enormous prestige provided substantial security - from indigenous opponents and the French - as he moved downriver to the ceremonial capital of Futa Toro, Hore-Fonde, and made it his base of operations for several months. The "establishment" of the Almamate could not oppose him openly. They argued that Futa was already a Muslim society and that its inhabitants did not need to leave home in order to find "true" Islam. Umar countered their claims by showing the failure to practice Islam fully, the "pollution" which came from "association" with the French, and the greater urgency of the "jihad against paganism" in the east.

One version of the debate is taken from an interview with an important oral historian of Futa, Hamady Sayande Ndiaye, in the 1960s. It takes the form of a trial between Umar and one of the main leaders of the Almamate, a certain Cerno Falil Talla. It takes place in Hore-Fonde, and the audience serves as a kind of chorus and judge of the positions. A French commandant mentions a similar encounter in the archives, an encounter set in late September 1858. (Full interview can be accessed through the sidebar.)

Trial of Ceerno Falil in Futa Toro

He [Umar] headed back to Fuuta,

This was when he came and told Fuuta to emigrate.

He spent the rainy season among them in Hoore-Foonde,

He stayed there until the hot humid season started.

It happened that they were trying to deceive him,

they had resolved to betray him.

He however stayed, he was praying to God for them

until the arbitration between him and Ceerno Faalil.

That was when he sued Ceerno Faalil and won his case.

He said he had found in the country that the Fuutankoobe,

learned and followers alike, failed God in ten ways.

In ten things they were disobeying God.

They called him to justice.

They said that now he must tell them the ten things he spoke of.

If he won the case against them, they would be punished.

If they won the case against him, he would be punished.

He said: “All right!”

He said they should choose a judge. They chose a judge.

He said they should choose defendants. They chose defendants.

Ceerno Faalil then said he would be the defendant.

They chose the cleric of Aanam Siwal, he was the judge.

They said now he should speak.

They [Umar and Ceerno Faalil] got down and knelt [before the judge].

He said that he had found in the country

that they would allow a male [to wait] until the age of twenty

to be told he should be circumcised.

In fact, once a man is twenty, [he should no longer] be circumcised

or be stripped before another man.

He asked whether they did it that way, they said they did.

He said: “Is it forbidden?” They replied: “It is forbidden.”

....He said that God had declared:

“The mosques belong to me.

Your homes, keep them. Your fields, keep them. Your wealth, keep it.

But every house that you build for me belongs to me [forever].

Anyone who would pretend to share that house with me, when he dies,

I will make him enter the eternal fire.

Anyone called to lead prayer, when he has served as imaam and finished,

and if he has fathered a son who has not let prayer nor studied,

[this son] will claim: “This mosque is the mosque of my father,

or it is the mosque of my grandfather.”

But God has said that no one should claim that.

He asked: “Do you do this or do you not?” They said that they did.

He asked: “Is that forbidden of permitted?” They said it was forbidden.

He said: “Therefore it is not the [right] path that you are on.”

The cleric had lost.

He [Umar] told him to lie down and be beaten.

He [Faalil] lay down, but called in a great spirit who lay on his back.

They whipped him twice with cords.

The third time he [Umar] said: “Bring me the cord!”

It was given to him. He told the great spirit: “Get out of there!”

The great spirit left.

He whipped the man twice. He [Faalil] screamed.

He [Umar] asked: “My Lord, it is you that he denied, show him Hell!”

The ground split, he [Faalil] saw Hell and cried out.

They asked him: “What is it?”

He replied: “I have just seen Hell. God just showed me Hell.”

He [Umar] said: “Stand up and look at the sky.”

He looked at the sky, he saw the reflection of heaven.

He continued: “Do you still say that I do not surpass you?”

He replied: “You do indeed surpass me Taal!”

He [Faalil] stood up abruptly, swore allegiance, and gave him his hand.

83 persons submitted on the spot.

Each one there was joined by his family.

This was the beginning of the migration.

People came in steadily until he arrived in Nabbaaji.

From Nabbaaji on it was a matter of coercion.

Recruiting an army of jinns

What I am going to talk about here are the great deeds of Sayku Umar.

...Now as to the reason for his stay in Hoore Foonde,

Everyone knows that he spent the rainy season in Hoore Foonde,

But in fact he spent the rainy season there for a particular reason.

People do not know why he was traveling there,

But as for him, he knew what he was going [therek] for,

At that time he was recruiting an army,

But the army that he was recruiting was an army of jinns.

...While the town slept, he would slip away to a small hill called Gemmi.

The chief of the jinns lived there, at a place called Koylel Tekke.

He would go there, spend the night talking with him

Until the morning prayer, then return.

The people would see him in Hoore Foonde as he arose in the morning,

Without knowing where he spent the night.

In fact each time he was with the chief of the jinns

He was Actively planning, asking him for an army to aid [the holy war].

He agreed to give him an army, but told him to be patient.

What he meant by being patient was that he had to recruit the people

for the army he would give him.

Some were in Casamance, some were in Jolof,

some were in Siin Salum, some were in the east.

Throughout the whole rainy season he [Umar] stayed there,

while he [the chief] was sending messages to them

that they come, that he had a plan to work out with them.

...One day he waited until late at night, when people were sleeping.

He got up, he went to the chief of the jinns.

The chief of the jinns told him:

“Now I have decided to give you an army, the army has come.”

He gave him what must have been 100,000 jinns together with their guns.

Umar succeeded in his massive recruitment. Against great odds, he conquered the mighty kingdom of Segu in a series of battles between 1859 and 1861. He then entered the capital and the palace of King Ali, who had already fled to the Caliphate of Hamdullahi. He organized a public burning of the "fetishes" of the chief priest and king - as a way of identifying Segu as "pagan" and marking the advent of Islam. The Segu triumph was the culmination of the "jihad against paganism."

Segu had been a powerful force for almost two centuries, extending its influence to the south and the west, with a deep involvement in slavery and the slave trade in several directions. It contained Muslims and non-Muslims of various stripes, and enforced no particular religion, but its ruling class adhered to traditional Bambara customs. For Umar and other Muslims this was paganism, indeed arch paganism, and must be eliminated as the Western Sudan became a "land of Islam." This was the mission which Umar, pilgrim and leader of the Tijaniyya, now leader of the jihad, had given himself. The victories were a remarkable achievement for an army recruited hundreds of miles away and facing an enemy with a ferocious reputation. Muslim authorities from as far away as North Africa sent Umar their congratulations.

We have chosen two excerpts to show the importance of these events. The first, which we can call an internal source and label Triumph over paganism at Segu, comes from the same source used in the Praise poem of Umar Tall, that is the 'ajami poetry of Mohammadou Aliou Tyam, and it describes Umar's entry into the Bambara capital and palace. Umar is called the Differentiator, farugu, an echo of his name sake who was the second caliph after Muhammad. Like Caliph Umar, Shaykh Umar could differentiate between good and evil, Muslim and pagan, devout and hypocritical. He keeps the idols or "festishes" of Segu to serve as proof of the religious identity of the ruling class in his growing dispute with Masina and the Kunta (see below).

Triumph over paganism and the idols of Segu

The country of Segu came forward, converted, all submitted [to him].

He built mosques throughout Segu, no one could deny [God] any more.

...The Shaikh brought out gold and silver, all

Was distributed to the two Futas, and the women, completely.

The Differentiator tore down every part of the house of idols until it was ground into dust,

the idols themselves were preserved to reinforce a future argument.

Congratulations from the Moroccan Tijaniyya

...Our ears have been delighted by this good news about you and your majesty - good news which when heard makes people happy, and whenever a Muslim hears it he is cured of his envy and raises his voice and is filled with joy and praise. It is news of victory and conquest, the news of clear glory, a great victory, a source of much joy. In truth this is a glory for the Muslim nation, a victory through a road that had previously been blocked, it is a joy for the saints of God who repeat it standing and sitting. I pray that the swords of truth will strike the foreheads and cheeks of the evil people. When the news became public knowledge and we got the details from all sources, it became necessary for us to come to your doorway with the congratulation.

Therefore we thank God who, through you, has removed obstacles, and helped to spread your message, and through your happy rule set in order what was confused and destroyed the evil people. Be happy, O master in the bounty of God. May your days be happy with God’s happiness....

We have written this on the fifth of Rabi` II in the year 1277 AH [21 October 1860].

The Jihad that Became Fitna

As we have said, Umar's emphasis throughout the "jihadic period" was not resistance to the Europeans but the "destruction of paganism" in the Western Sudan. Or at least it was until he conquered Segu in 1861, and discovered fully the complicity of the Hamdullahi regime and the Kunta Muslim network in the support of Segu against the Umarian jihad.

From the time of his campaigns against Kaarta in 1855, Umar became aware of the opposition of Hamdullahi, now led by a young caliph Amadu mo Amadu. Masina sent an occasional army to slow Umar's advance, and by the late 1850s prepared a more concerted resistance, in conjunction with the Kunta and their leader, Ahmad al-Bakkay. This resistance included an arrangement for the conversion of the Segu king to Islam. On this basis Hamdullahi and the Kunta could claim that Segu was now Muslim and not a suitable target of the Umarian jihad.

Umar discovered in the palace of King Ali a considerable correspondence between Ahmad al-Bakkay, Amado mo Amadu and the Segu king. This proved his contention about the complicity of these ostensibly good Muslim leaders - the Fulbe caliph in Hamdullahi and the Kunta scholar in Timbuktu - with an obviously pagan ruler of the Western Sudan. Umar was furious, and spent the next year corresponding with Hamdullahi, demanding an apology and the surrender of King Ali, and composing a text which showed the complicity and how it contradicted the norms of Islam. He went so far as to invoke the concept of takfir, "excommunication" or apostasy, and applied it to the caliph and his court. This meant that in his eyes Hamdullahi was no longer Muslim, in which case it was a suitable candidate for jihad. The document, bristling with references to the Quran and Muslim authorities over the centuries, was called the Bayan Ma Waqa`a d’al hajj Umar, and served as a justification for the military campaign against Masina launched in 1862. Here we take brief excerpts from the very last part of the Bayan; Umar is summarizing his points against the caliph.

Accusations against the Caliphate of Hamdullahi

First, there is the manner in which he hid the polytheists [Bambara] from the eyes of the Muslims by pretending that they had converted and using that argument to explain why he rejected fighting them....Second, there is the manner in which he sowed confusion among the Muslims by listening to the infidels and believing in their conversion....Third, in acting thus he showed that he prefered the domination of paganism to the rule of Islam....Fourth, there is the manner in which he seized the property of Segu [to hide it from us], knowing that this is forbidden by the Qur’an, the Sunna and the consensus of the authorities....Fifth, there is the manner in which he sought temporal power, always the source of disaster, and the things of this world, by detestable means such as lies, treason and flattery of the pagans....Sixth, there is the manner whereby he sought to trace a path between infidelity and the faith by sending and army to aid the infidels against the troops of the believers....Seventh, there is the manner by which he abandoned all restraint and Islam, by openly mixing his troops with those of the enemies of God....Eighth, there is the manner in which he sowed confusion among the Muslims who were with him; he lied to them by his speech and by the ruses employed, lies told and fables invented....Ninth, there is the manner by which he defended the legality of combat between Muslims and the blood shed [by Muslims]....Tenth, there is the manner in which he undermines his own case and shows that he is not one of the faithful but rather grouped with the hypocrites....

But things rapidly fell apart, beginning with the defeat of the main Umarian army near Timbuktu and a revolt and siege of the Umarian forces in Hamdullahi itself. Early in 1864 Umar and a handful of supporters escaped to the cliffs of Degembere to the east, but there they succumbed to the Masinanke pursuit. Umar's nephew, Ahmad al-Tijani, did survive, and from his center in Bandiagara managed to resume the recapture of Masina - at great cost in lives and livelihood - over the next 25 years.

I have called the whole attack, revolt and recapture the first fitna of the Umarian movement. Fitna means struggle or civil war, and it is the term which the early Muslim community of the Arabian peninsula used to describe the conflicts which resulted in the division between Sunni and Shia Islam. The Umarian-Masinanke struggle put Muslim authorities throughout the Western Sudan in a very awkward situation: here two Muslim Fulbe regimes, both ostensibly reform-minded, were pitted against each other. The campaign to "destroy paganism" was forgotten, as well as the mission to spread the practice of Islam. And it left Umar's oldest son and successor, Ahmad al-Kabir, with a huge set of problems.

Related Content

Interviews

Interviews Documents

Documents- Accusations against Hamdullahi

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

-

Accusations against Hamdullahi

- Congratulations from Morocco

Congratulations from Morocco

-

Congratulations from Morocco

-

Congratulations from Morocco

-

Congratulations from Morocco

- A critique of the Umarian movement

A critique of the Umarian movement

-

A critique of the Umarian movement

-

A critique of the Umarian movement

-

A critique of the Umarian movement

-

A critique of the Umarian movement

-

A critique of the Umarian movement

-

A critique of the Umarian movement

-

A critique of the Umarian movement

-

A critique of the Umarian movement

-

A critique of the Umarian movement

-

A critique of the Umarian movement

-

A critique of the Umarian movement

- Praise Poem of Umar Tall

Praise Poem of Umar Tall

- Triumph over Paganism at Segu

Triumph over Paganism at Segu

-

Triumph over Paganism at Segu

-

Triumph over Paganism at Segu

-

Triumph over Paganism at Segu

- Verbal portrait of Umar

- Warning to Muslims in Saint-Louis

Warning to Muslims in Saint-Louis

Maps

Maps- Umar Tall's Probable Pilgrimage Route (1828-1830)

Umar Tall's Probable Pilgrimage Route (1828-1830)

- Umarian Domain, 1862

Umarian Domain, 1862