Failed Islamic States in Senegambia

David Robinson

The Madiyankoobe

Introduction

The Battle of Samba Sadio, 1875

Islam, like Christianity, has a strong emphasis on the beginning, middle and end of time. The end of time involves judgment and cataclysmic conflict between the forces of good and evil. For Christianity this “eschatological” thinking comes especially in the Book of Revelation. For Muslims it is spread out in the Quran, and it centers around a figure called the Mahdi, the “rightly guided one” who will appear at the end of times and guide the faithful through the perils, accompanied by another force for good, Isa or Jesus. Many Muslims thought that the end of time might be coming as their world fell more and more into the embrace of European domination and modernization, in the course of the 19th century. The Mahdi of the Sudan (d 1885) is the best known of these figures, but pious Muslim reformers all over Africa and Asia began to look for the Mahdi as their world came under Western control in the late 19th century. We could say that Mahdism was reformism squared, or the impulse of reform subjected to extreme pressure.

One instance of this occurred in northwestern Senegal for a short but intensive period from 1867-1875. It may have had as much impact as the movement launched by Umar and continued by Ahmad al-Kabir - on the achievements and dangers of Islamic states, the decline of the traditional monarchies, and the emergence of Sufi movements. We give it the name of Madiyanke or Maadiyankoobe, “those of the Mahdi.”

But to understand this movement we have to go back to the father and his narrative 50 years before. Hamme Ba was a contemporary of Umar Tal. He was also from western Futa and received initiation into the Tijaniyya Sufi order. But in the 1820s, when Umar was making his overland pilgrimage, Hamme Ba was developing his critique of the ruling class of Futa - those who had succeeded Almamy Abdul as heads of state or grand electors of the region. At a certain point he escalated his criticism, claimed an appointment as the Mahdi of Islam, and apparently sacrificed one of his sons to demonstrate his devotion to God. The Futanke authorities, sensitive to the criticism and horrified at the sacrifice, exiled Hamme to the western fringe of the territory.

Hamme lived in relative obscurity after that, in a village called “Wuro Madiyu” in this border area. He did circulate in northwestern Senegal, in both Haal-Pulaar and Wolof areas, and made a strategic marriage to an important maraboutic family in Coki, a relatively autonomous Muslim town in the region of northern Cayor called Ndiambur. His children, including the Madiyanke leaders Amadu and Ibra, were comfortable in both the Pulaar and Wolof languages and moved easily back and forth across the region. The Ba maintained their Tijani affiliation, but it was not very prominent in their lives - in contrast to its role for Umar and Ahmad al-Kabir.

When Umar was recruiting in Futa in the late 1850s, Hamme supplied information to the French about his movements. In the late 1860s his sons - especially Amadu and Ibra - launched a new critique of the traditional authorities, Futanke and Wolof, the French intrusion and the cooperation between traditional and colonial authorities. The occasion was the outbreak of a devastating cholera epidemic in 1868, an epidemic that probably took 25% of the population along the river valley. The Madiyanke took the epidemic as a divine judgment against corruption and the collaboration of the ruling classes of northwestern Senegal.

The Madiyanke brothers established their main base in Jolof, a Wolof-speaking kingdom equidistant from Coki and Ndiambur, on the one hand, and western Futa and Wuro Madiyu, on the other. They easily displaced the traditional monarchy of Jolof, made some effort to establish an Islamic regime, and exerted considerable influence along the whole river valley - perhaps most especially in western Futa and Toro province, the original home of Umar and Hamme Ba. Their critique of the corruption of the ruling classes and their collaboration with the French echoed the positions of Al-Hajj Umar and resonated among many of their contemporaries. In 1873, however, they earned the enmity of many Muslims throughout the region, and severely tarnished the image of the Islamic state.

The Massacre at Pete

In the 1870s the Madiyanke continued to move easily throughout northwestern Futa and to challenge the local and regional authorities. In 1873 their agent was returning from central Futa with a supply of horses and cloth when he was killed by followers of two prominent Futanke, Ibra Almamy Wan of Mbumba and Mamadu Siley Anne, an elector and head of the important town of Pete. The Madiyanke responded quickly: their followers went to Mbumba, where they were denied entry, and then to Pete, where they were able to get in. They accepted hospitality and then, on a common signal, killed their hosts. Some 170 persons died. The Futanke were reminded of what the father Hamme had done 50 years before. They forced the Madiyanke out of the central and western regions, and began to mobilize a coalition in opposition.

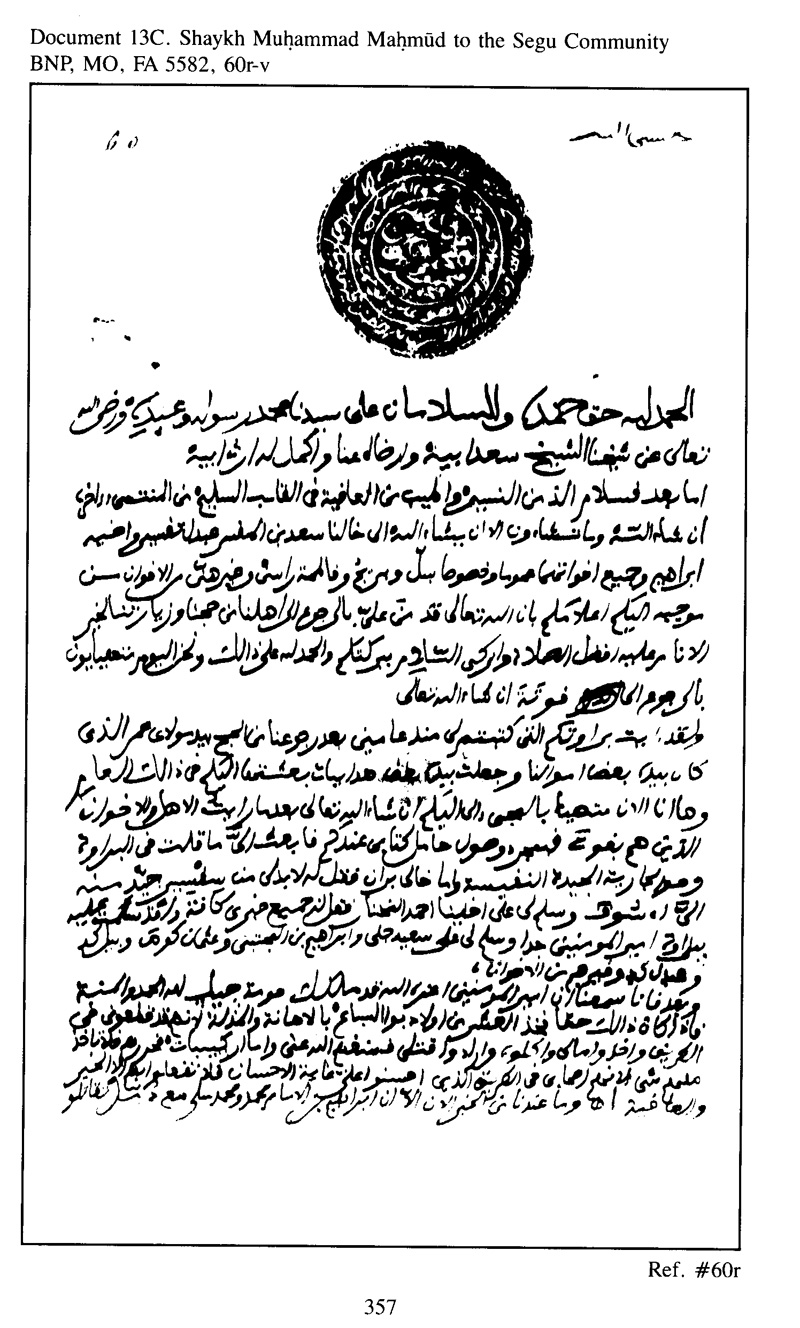

For versions of this horrible event, we go first to a letter which an important cleric of Futa and Saint-Louis wrote to the leading notables of Segu, the capital of Ahmad al-Kabir, in 1874. Shaykh Muhammad Mahmud Kane was a descendant of Almamy Abdul and son-in-law of the chief judge of the Muslim Tribunal established by Governor Faidherbe in Saint-Louis, which is to say he was well connected to the Futanke aristocracy and to the French colonial authorities. He had performed the pilgrimage to Mecca and was a leading Muslim scholar and Sufi in his own right. His letter is heavy on greetings, and congratulations to the Commander of the Faithful Ahmad, but eventually gets to the burden of the events.

The massacre at Pete, an Arabic letter

...We are writing to you to inform you that God Most High has favored me by [allowing] me to return to our people from our pilgrimage and our visit to the best of mankind [the Prophet Muhammad] (upon whom be the best of blessing and the purest peace). This was accomplished through your baraka, praise God for this....And greet for me with joy the Commander of the Faithful and Seydu Jeliya...and the other brothers....

What we have now in the way of news is that Ibra Almamay Muhammad [Biran Wan] and Muhammad Sile [Anne] together with the Damel fought with a great force against Ahmad Mahdi who claimed that he was Jesus (peace be upon him), and that his father was the Mahdi. Ahmad continued his war against them, but now the Governor of Ndar together with his forces has resolved to join with them [Ibra and Muhammad Sile] in order to attack him and expel him from the land, and they will kill him if they capture him....

Now the cause of the two sides entering into this enmity is the terrible thing which was done by him [Ahmad] in the first year to the people of Pete, when they [the Madiyankoobe] betrayed them and killed more than sixty men. They came among them on the basis of safe-conduct. They stayed in the compounds until each one of the guests overpowered the host where he was staying and killed him. You have surely heard of this before now. They are now in the throes of a real war.

Tell the Commander of the Faithful that [on the way back from the pilgrimage] I came with three men from the west from the city of Fez, who are disciples of Shaykh Ahmad al-Tijani and wish to visit him....Written in Ndar on the 11th of Dhu’l-Qa`sa 1291 [20 December 1874].

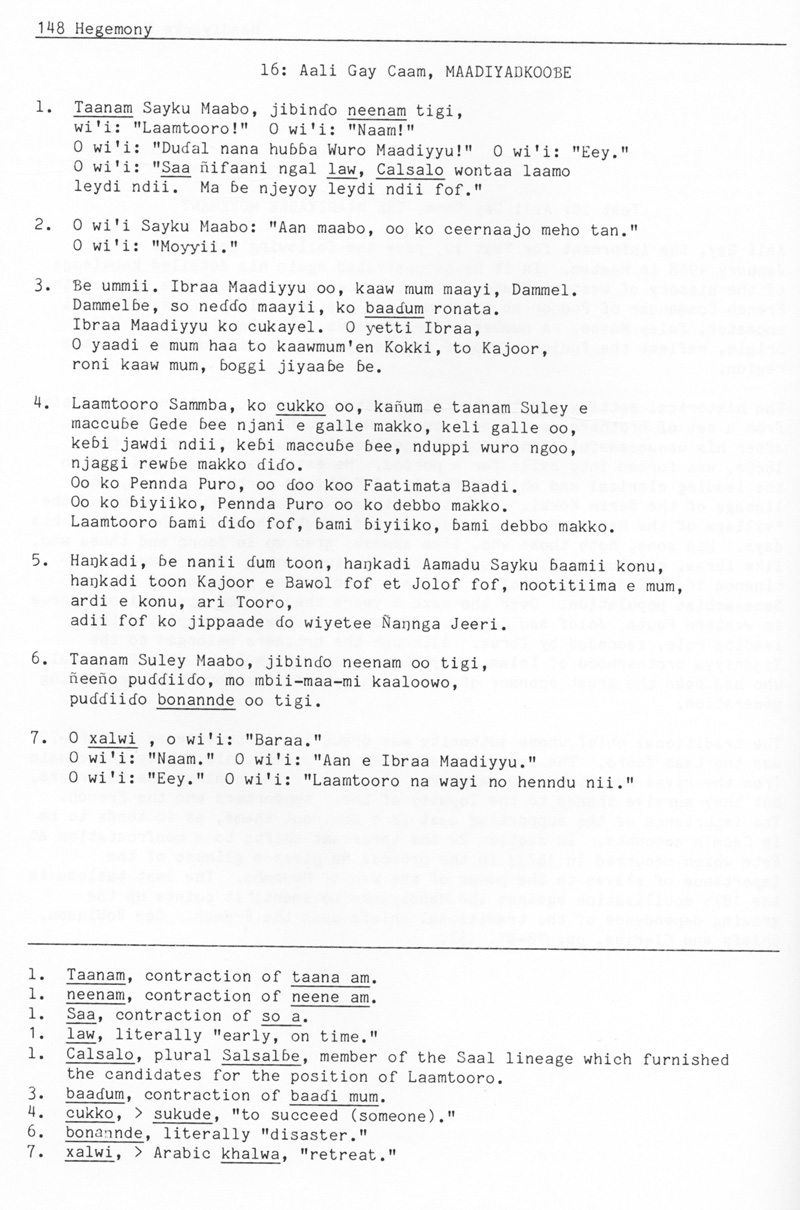

The second account comes from an interview with a Futanke oral historian, Ali Gaye Thiam. Ali Gaye puts his story into the perspective of a fellow griot who was a counselor to the leaders and participated in the events, Sayku or Suley Maabo. Thiam, himself a griot of the maabube group, begins with the confrontation of the reformers with an important and French-connected chief of western Futa, Lam Toro. At the time Muulee Saal held the position; he was considered relatively ineffectual. His deputy was a much stronger figure, Samba Umahani Saal, and it is to him that Suley Maabo directs the warnings about the dangers posed by the Maadiyankoobe, those of “Wuro Madiyyu.” Ali Gaye then moves on to the Pete massacre. Note that he puts it before the confrontation in Mbumba, where Ibra Almamy is able to avoid a repetition of the killing. And note that neither of our sources sees much of an element of reform and islamisation among the “reformers.”

The massacre at Pete, account # 2, in interview

My grandfather Sayku Maabo, the very one who fathered my mother,

said: “Laamtooro!” He replied: “Yes.”

He said: “A hearth is burning in Wuro Madiyyu.” He said: “Yes.”

He said: “If you do not put it out quickly, the Saal will neverl rule this

country again. They will turn the whole country into their possession....

As for them [the Maadiyankoobe], they had left secretly,

they came, fell on his compound [in Gede],

set fire to the house, burned seven granaries down,

killed his slaved name Sule, and Ibraahima, Maamadi and Maamuud,

they took forty head of cattle and slaughtered them all.

They rode back, got down and came (in)....

After that Baraa [and the other brothers] went back, headed for Jolof,

fought against Jolof and won. They stayed there about six months,

then they chose someone and told him to come search for horses.

He was called Sammba Njaay Beey, he had a donkey

Loaded with plenty of silver, they tarried at Pete.

Sammba Njaay was the son of a chief,

but he acted as though he were mentally ill.

They said that it was the people of Pete who killed him,

and that caused the attack on Pete.

They took their goods, rushed back and informed their cleric [Aamadu],

That day in Pete no one was left, because he ordered

that day for each one to kill his host.

They continued on, he marched on Mbummba.. He found Ibraa at home.

Ibraa had learned he was comming, his compound had been prepared with holes

dug into the entire wall, at each hole was posted a slave.

He [the cleric] got up, approached the mosque, came, stopped at the mosque.

He told Ibraa to come so that they could greet each other,

since he was his guest.

Ibraa said yes, and asked him to wait a bit until he came.

They complained that Ibraa was late, was stalling.

Ibraa then came out flanked by 600 guards,

ordered each of them to aim at someone’s head, they were [his] slaves.

He [the cleric] saw this, knew it was not worth doing, and went on.

The Battle of Samba Sadio, 1875

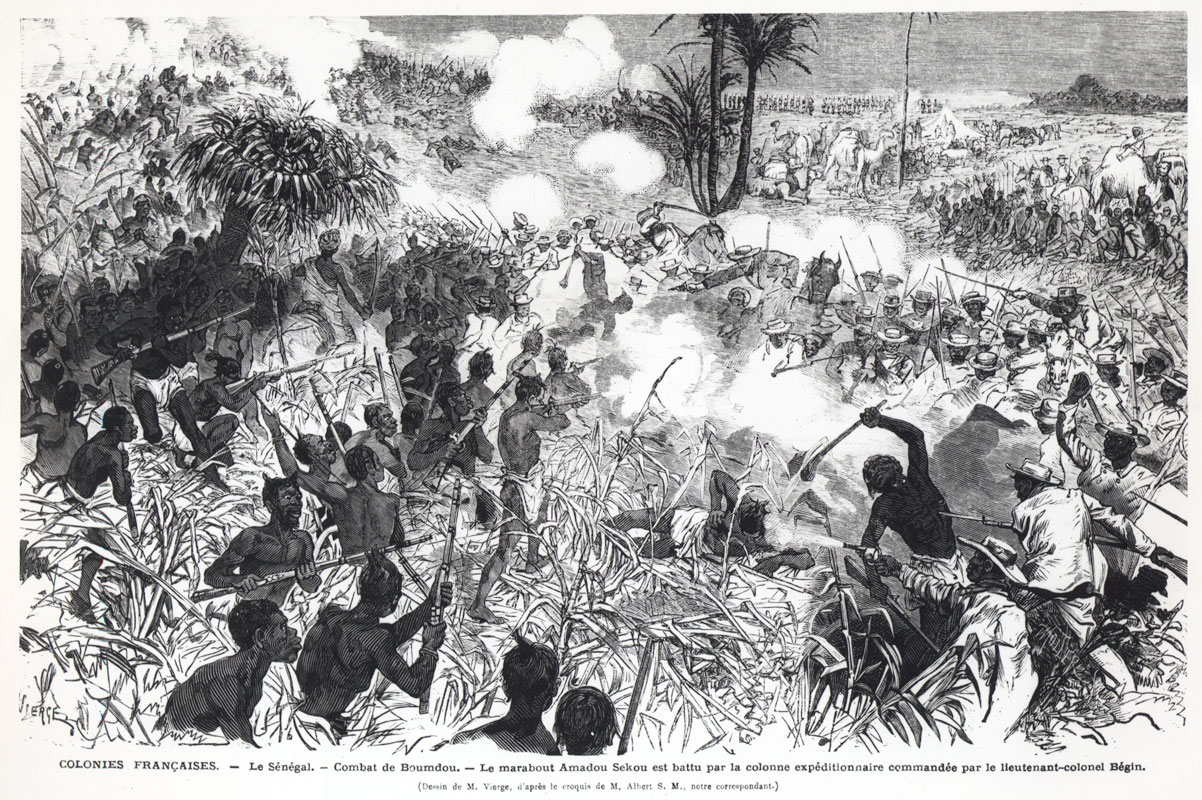

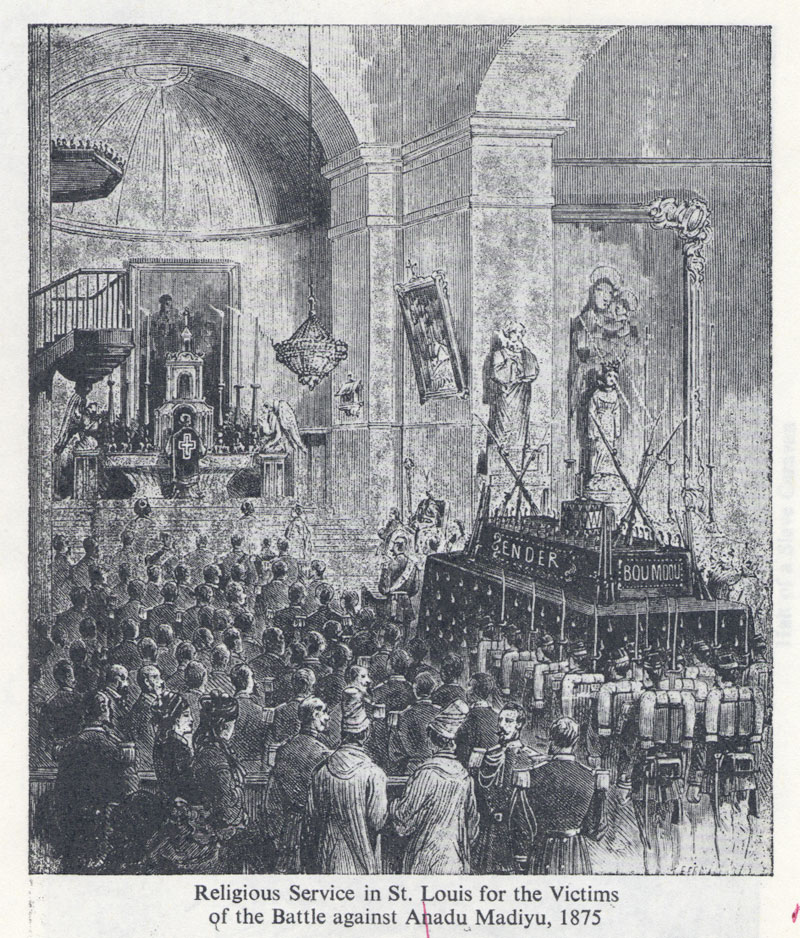

After Pete the Madiyanke forces pressed from Jolof into the region of Ndiambur and the grain producing area near Saint-Louis. They threatened the monarchy of Cayor, under Damel Lat Dior as well as the French. The two sides, alternatively friends and enemies from the 1860s to the 1880s, formed a coalition and confronted the Muslim army near Coki in February 1875. After hours of combat, and a heavy toll on both sides, the coalition prevailed, killed Amadu, his brother Ibra, and the overwhelming majority of the Madiyanke followers. The threat ended and the survivors dispersed. Over the next few years some of them emigrated to the east to Nioro, to join the Umarian forces there. A French artist has given us an engraving of the battle and a picture of the service of commemoration for French victims of the conflict.

Some Madiyanke survived the battle of Samba Sadio and fled. Others were captured by the Senegalese members of the victorious coalition and treated as property, that is, as slaves. In the early 1880s two scholars debated whether their enemies were Muslim or not, which is to say enslavable or not. On one side was Madiakhate Khala, the venerable qadi of Lat Dior. He said that since the Madiyanke had made excessive and false claims about their status within Islam, the prisoners were apostates and the owners were justified in treating them as slaves. On the other side was Amadu Bamba Mbacke, the emerging Sufi leader and founder of the Murid order. He affirmed the Muslim identity of the prisoners, since they came from a Muslim heritage. The more tolerant position of Bamba would become the hallmark of the Sufi societies that dominated Senegalese Muslim practice under French rule.

Related Content

Interviews

Interviews Documents

Documents- The Massacre at Pete 1

The Massacre at Pete 1

-

The Massacre at Pete 1